'I'm broken, fix me. Tell me how I stop gambling'

The Gordon Moody rehab centre is turning around the lives of chronic addicts

It is an ordinary Victorian house on an ordinary south London street but powerful things happen here – it is a place where lives are transformed, even saved.

The house is run by the Gordon Moody Association and is one of their two centres that rehabilitates the most chronic gamblers. Their houses – the other is in Dudley in the West Midlands – are the only residential centres in Britain that treat solely gambling addiction.

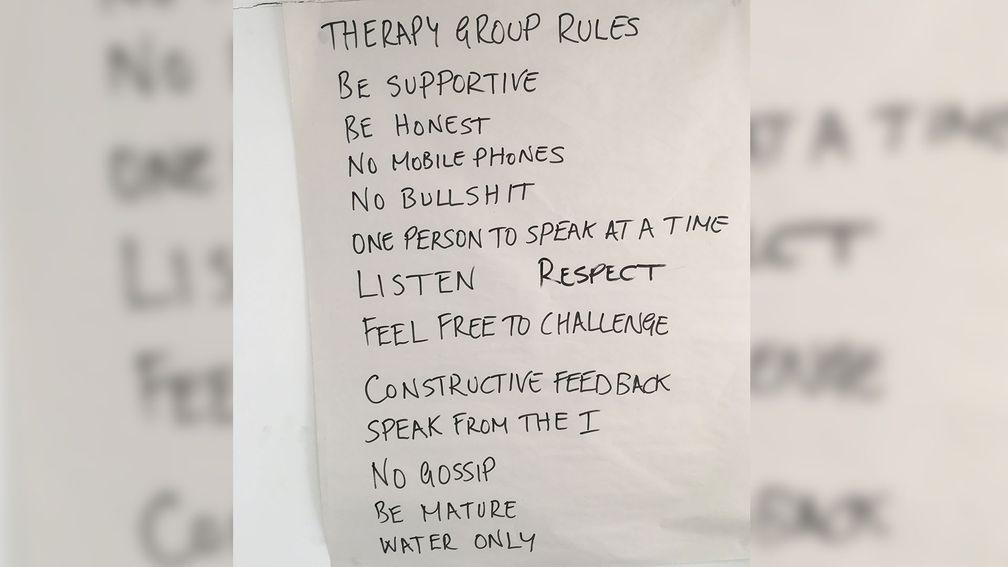

The Gordon Moody Association does not believe in quick-fix, temporary cures. Courses last 14 weeks and are intense. When you walk through the door you give up your mobile phone and all contact with the outside world and its manifest betting temptations.

Most importantly, when you enter it is to turn your life around. Those who arrive are desperate; they have usually lost everything, home and family. They will be deep in debt. A third of them will have considered suicide.

They are lucky to be there. The waiting list has more than 100 names and there are only nine beds in each treatment centre. Gordon Moody does not need to advertise. Unlike drug or alcohol addicts, clients are not usually referred by health professionals but have sought help, maybe after a lifetime of gambling, when they have finally realised this is the only way to save themselves.

For once, their luck really has changed, because this is a course that works. "People find us. They're in trouble and they find us and they generally see the programme through," says Adele Duncan, CEO of Gordon Moody and the driving force behind the operation.

"We have a high completion rate, 60-70 per cent," she adds. "People come to us because they've decided they want to engage. If some think 'I'll come for a couple of weeks, get cured and go home again' they won't last the course."

Getting into a Gordon Moody house is not easy. "First there is an online application to assess their level of need, then a panel to assess if they're suitable. We'd look at all the risk factors.

"They need to be relatively stable. No recent suicide attempts. They arrive with a certain level of anxiety, partly caused by coming here, by owning up, facing up to things. They might have life issues for which gambling is an outlet. We're stripping all that away from them.

"The first two weeks are to see if they'd be suited to a residential course. They have to be able to fit in.

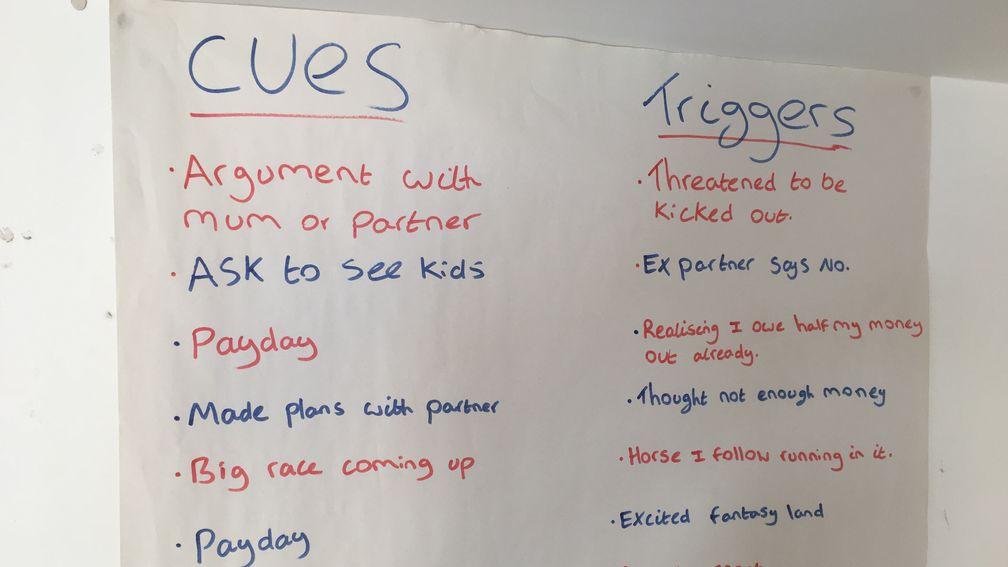

"First they have a 'life audit', an in-depth exploration of their history, from birth, of what has brought them here. This can be traumatic, but it gives real insight into gambling-type behaviours early on, which might have been family focused, triggers which have led to severe gambling.

"The majority get through the assessment but for some it's just not the right time. If they're not ready, they're not going to engage and the programme isn't going to work for them."

How do staff know they're taking in those who need this high level of care? "If they don't need it the other guys soon find them out and the staff will too.

"Our staff are pretty experienced. People come in and say 'you've never seen a gambler as bad as me; never seen someone who owes as much as I do'. Well hello, welcome to eight other men who are pretty much in the same boat. What you can afford to lose and what someone else can afford to lose may be different but the principle is the same – you got out of your depth."

And who are they? "All ages, but the average is 25-34," says Duncan. "We've had enquiries from as young as 17, but we take only over-18s and the youngest we've accepted was 20. Then there are some in their eighties who have been gambling all their lives.

"They are predominantly white British, which may be to do with culture but is something we probably haven't spent enough time looking at."

The residential courses are for men only. An increasing number of women apply but are directed towards the mixed model which involves days of intensive residential therapy and then periods at home with support by telephone and Skype.

"With that we're able to see many more people," Duncan says. "There are four courses a year, three for women and one for men, and each takes 10-13 people.

"We had a women's treatment centre but women often can't get away for 12 weeks because of childcare.

"When the guys arrive they spend two weeks settling in, finding ways to open up and talk, to deal with things in a way they never have before in one-to-ones with therapists and group discussions.

"For men it's difficult to share feelings. Women are much more open and empathetic, wanting to help each other. The men are more 'I'm broken, fix me. Tell me how I stop gambling.'

"They have to tell us what they owe and when they look it up it's astounding, hundreds of thousands of pounds in many cases. They have to take responsibility for that and we have to help them manage it – how they're going to pay off their debts, set up agreements with those they owe.

"Our job is to bring hope and to help them find ways to change their behaviour. It might take years to pay off their debts but even £5 a week is a start.

"When they come here they get £70 a week and their rent paid by housing benefit. Some might have been earning £150 grand a year but they still get only £70 a week. They have to learn to budget because they've lost any sense of the value of money. Once they've built up a big debt they think the only way to pay it off is with one big hit.

"It's about changing their thinking. They've lived with lies, lies and more lies. When they come to us they're completely deluded. They believe their own lies.

"During the week each session has a focus: assertiveness, honesty, dealing with anger, aggression, relapse. We do 'What does a gambler look like? Is a gambler James Bond? What is your perception of a gambler?' One of our male staff does a session on masculinity, 'What does it mean being a man?' It gives them a chance to talk about things most men don't talk about; their place in society as a man, who they look up to.

"They have homework to do but there are also film nights, bowling, activities around wellbeing. They have to take part in yoga, it's part of the programme."

It's a strictly enforced regime, but with good reason. Visits from family and friends are not allowed but they can phone once a week, although calls are supervised.

"Bear in mind they have no money, no phone, no access to the internet, no means to do things they shouldn't be doing," Duncan says. "If they go to the gym or go swimming they have to go with a buddy, someone who's further ahead in the programme, a role model to open up to. They're not allowed out the front door by themselves."

"Some of it needs to be fun; it's 12 weeks in rehab, 14 weeks in all, a quarter of the year, but for people who've been gambling for 20 years it's nothing, is it?

"They would say they wouldn't want it any shorter. Some feel quite anxious when they have to leave to face the world and we have halfway house options, but this length of programme seems to work. If there were just two six-month programmes a year we wouldn't get as many people through and we have to meet the need."

How do they measure success and can they be sure the programme has worked? "We have a number of assessment tools and we look at the whole person, their health, mental health, family relationships, budgeting skills, not just whether they have stopped gambling. We follow up with aftercare checks, calls and visits from our outreach worker, ex-residents' meetings and one-to-ones. Of course some drop out but they know where we are if they want to come back to us.

"You can see the improvement, the physical changes and you know there are mental changes too. When they leave they're a different person so there is great reward in that. What keeps our staff going is that this really impacts lives.

"And it's not just their own. They're affecting their families, colleagues, neighbours, communities. These are not people living a quiet, normal life.

"In the treatment of substance misuse every £1 spent saves £4 and this is similar. We deliver value for money to society. Is it better to get 100 people through a different treatment model and they come back within a year, or 50 with us who can then sustain a normal life?"

Funding for Gordon Moody comes from the gambling industry, distributed through GambleAware. How does Duncan feel about that? "It's an unusual model. You don't find services for alcoholics supported by the alcohol industry and you certainly wouldn't take money from drug dealers to set up rehab.

"But we don't blame the industry for the people coming into our houses. Some gambling firms are keen to do the right thing and some are just ticking boxes. The good ones lead from the top. When people come in they may blame the bookmaker or casino but we try to help them take responsibility.

"Our responsibility is to raise awareness of gambling as an addiction. We have data coming out of our ears about how people gamble. The means have changed – with young people slipping easily from gaming to gambling and increasing numbers of students, when the loans come in, blowing the lot and having to drop out of their studies – but once you have an addiction you'll gamble on anything.

"Complete abstinence is the only way. You can't become a social gambler if you've been a pathological gambler.

"Many have to change careers because their jobs gave access to money or the chance to gamble all day. We get guys who come back as part of our outreach service and stay with us. They say, 'You've saved my life, I want to give something back'. Our reply is, 'You've done the work, we just helped you'."

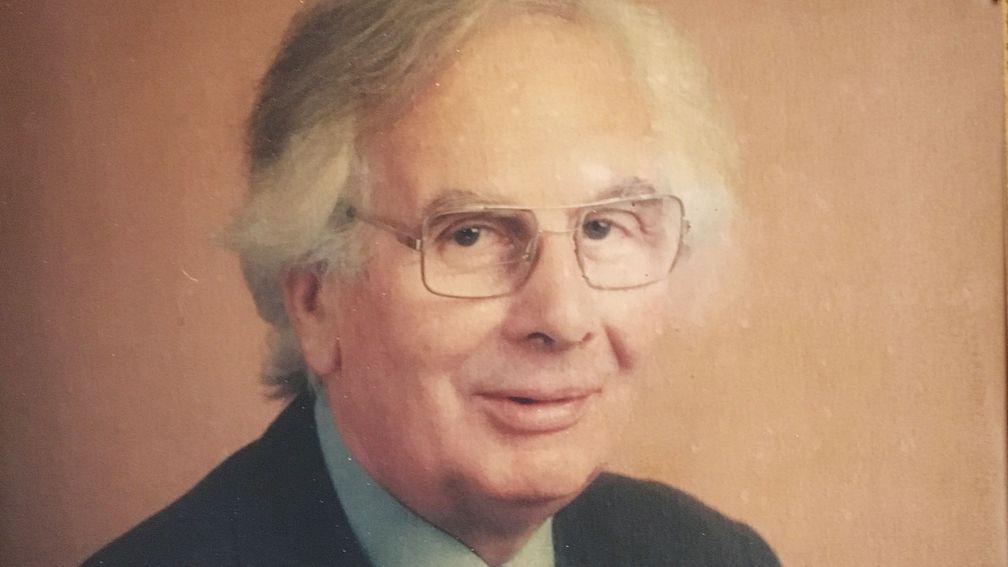

Who was Gordon Moody?

Born in 1912, Gordon Moody was a Methodist minister who in the 1960s set up the first British branches of Gamblers Anonymous, an idea flourishing in the US. He realised the gamblers who were coming each week to GA were struggling to get the support they needed between meetings as well as suffering housing problems as they were gambling away their money. He set up the first hostel, Gordon House, in 1971. He was appointed MBE in 1969 and died in 1994.

More great reads for Members Club subscribers

Manchester racecourse remembered 56 years after its last race was run

Breeders' Cup legend Arazi thriving at 30 as the fan mail keeps pouring in

If you are concerned about your gambling and are worried you may have a problem, click here to find advice on how you can receive help

- Ladbrokes owner Entain reports fall in online revenues as regulatory challenges continue to bite

- Watchdog warns Spreadex-Sporting Index merger raises competition concerns following investigation

- Entain chairman Barry Gibson to step down in September as search for new chief executive continues

- Analysis: Flutter and 888 have enjoyed contrasting fortunes but they still have things in common

- US arm FanDuel drives 'best in class' Flutter Entertainment forward, with more growth forecast for 2024

- Ladbrokes owner Entain reports fall in online revenues as regulatory challenges continue to bite

- Watchdog warns Spreadex-Sporting Index merger raises competition concerns following investigation

- Entain chairman Barry Gibson to step down in September as search for new chief executive continues

- Analysis: Flutter and 888 have enjoyed contrasting fortunes but they still have things in common

- US arm FanDuel drives 'best in class' Flutter Entertainment forward, with more growth forecast for 2024