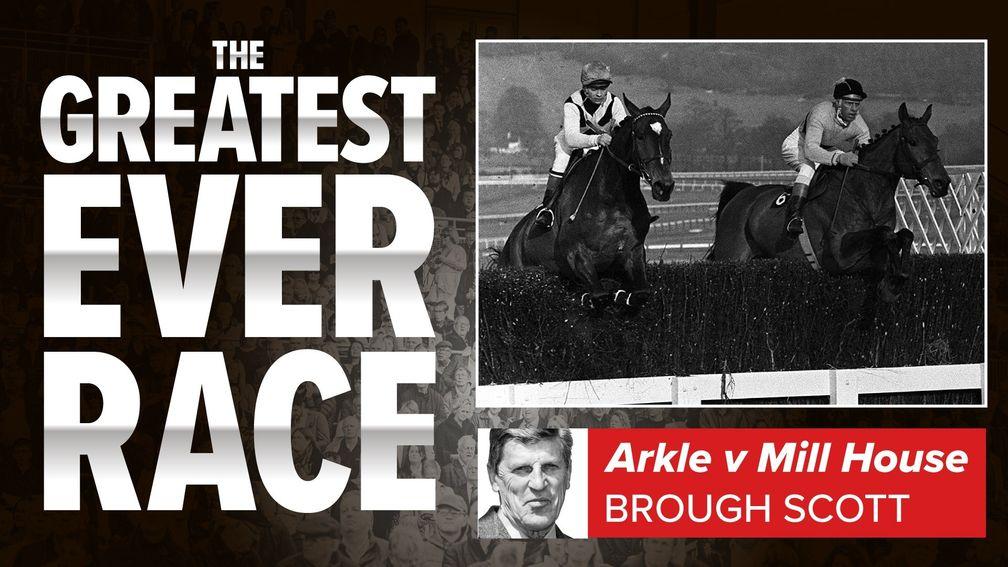

Two great champions, two colossal reputations - only one could survive

Voting has now closed for The Greatest Ever Race but you can still read our ten fantastic articles. Below, broadcaster Brough Scott nominates Arkle v Mill House in the 1964 Cheltenham Gold Cup. The winner will be announced at racingpost.com at 6pm on Saturday, July 23.

The day remains like no other. For it is what happened before as much as afterwards that still sets Arkle and Mill House's 1964 Gold Cup in a special category of racing heaven.

Never before, and certainly never since, have two such heralded champions come together for so anticipated a showdown. But while it was the start of Arkle's superstardom, it's easy to forget how much Mill House had been hailed as a second Pegasus. Why, hadn't he already put Arkle in his place four months earlier in the Hennessy?

"For us," wrote John Lawrence (Lord Oaksey) the next day, "he was what Shakespeare must have been to the Elizabethans on the first night of Hamlet, what Garbo was on the screen, Fonteyn on the Covent Garden stage, Caruso at La Scala, Matthews at Wembley, Bradman at the Oval."

Okay, John was dipping his pen in purple, but he himself had won the first Hennessy Gold Cup five years earlier, was the greatest racing writer of his or any era, and was only colouring what most of us were thinking.

For the sight of Mill House in full sail was something to wonder. He was big, black and handsome with a vivid white star on his forehead. He could look almost heavy in the paddock but out on the track he skipped over fences as if he had wings. Arkle's rider Pat Taaffe knew all about him for when Mill House moved to Fulke Walwyn he wrote to Willie Robinson, the stable jockey, to say that he would be riding "the best horse in Britain – and possibly in the world".

And Pat would know because he had jumped gates and walls on Mill House out hunting as a three-year-old before the horse went into training with Pat's father Tom, and Pat had been on board when Mill House won his first hurdle race the following March.

However, the early road to glory was anything but smooth. Bought during the summer by the over-enthusiastic Bill Gollings, sent to Syd Dale in Epsom, and ridden by the wholly unsuitable Ron Harrison, Mill House turned over at the first hurdle on his British debut, was pitched in against the Champion Hurdle winner on his second, landed a coup at Wincanton on his third and then, as a huge but inexperienced five-year-old, was sent out over fences where he and pea-on-a-drum Ron duly crashed out at the sixth.

Two months later the drums were still beating but heads were all shaking when Mill House reappeared at Cheltenham. This time he was to be in the strong, skilled and fearless hands of Tim Brookshaw. It was the day of my first ride on the track (if you must ask, Arcticeelagh and I finished third to Fred Winter!) and I remember watching awestruck as Tim pulled on the colours (sweaters, not silks, in those days) and went out to ride this errant monster with the same undaunted laugh with which he later faced his years of disablement.

Concerns over Mill House's jumping were immediately justified as he rooted through the first two fences with all the signs of a horse with confidence shot. Brookshaw was most famous for his implacable and now unacceptable force, especially at the last where his special trick was to get the whip going on take-off, mid-air and landing, but that day at Cheltenham was a schooling masterclass. Taking Mill House away from the others, he let him gradually regain belief, did not rejoin the field until the third-last, and then romped home so easily that we now shook heads not in worry but in wonder.

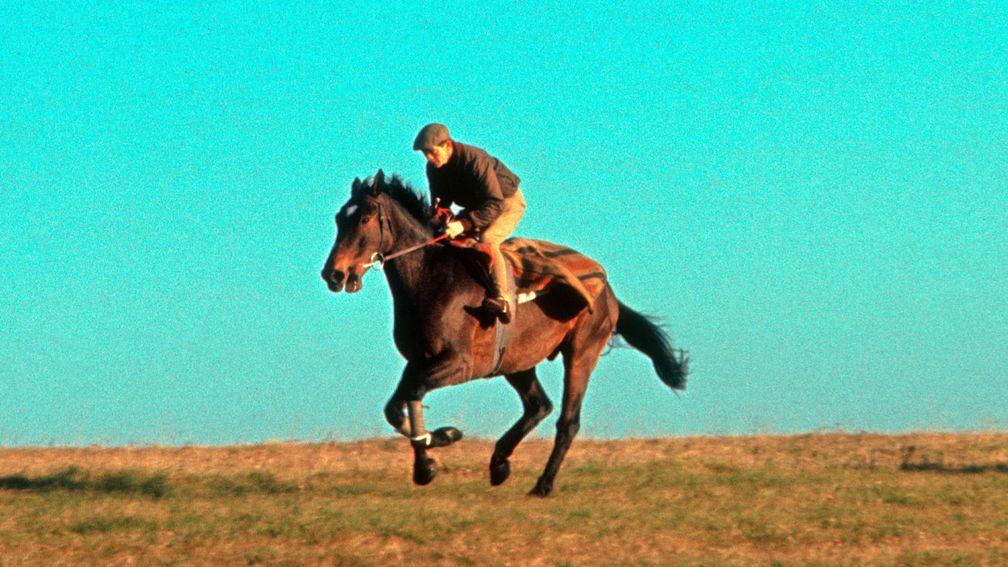

From there the legend only grew. During that summer of 1962 Mill House was moved to Fulke Walwyn in Lambourn, the finest trainer in Britain who had just won his second Gold Cup with the famous Mandarin. Soon there were rumours that Fulke, as well as Willie Robinson, was beginning to think that Pat Taaffe's letter was not too far-fetched and the joy of watching Mill House that winter, culminating in a spring-heeled, confidence-brimming return to Cheltenham for the Gold Cup, stays with us spectators still.

It was this dream that we carried into the Hennessy of 1963, Mill House's first run of the season. He was just six years old. He had it all before him. He was the galactico for which every fan always craves and yet we, and especially I, should have realised that there were already two Gods in that pantheon.

I remember exactly where I was when I first saw the other one, standing by the last for the Honeybourne Novices' Chase on Saturday, November 17, Arkle's first race over fences. I was a 19-year-old amateur already seriously affected by the racing bug and had no defence against the image in front of me.

We had been warned that the Irish thought this lean, greyhound-like, long-eared thing was a bit special, and what happened at the finish was a bit special. There were decent horses against him, but Arkle just skipped the fence and sprinted 20 lengths clear as if he were another species. Perhaps he was.

But despite that, despite the devastating display he put up at the Cheltenham Festival in winning the Broadway Chase (today's Brown Advisory) two days before Mill House's Gold Cup and three subsequent wins before the Hennessy showdown, we were still not convinced. And neither, to be fair, was the handicapper. That's why Mill House was set to give Arkle 5lb at Newbury and when he beat him eight lengths into third place we all assumed our smugness was justified.

Sure, some of the Irish were saying that Arkle had slipped badly three out, but it was one of those damp, soggy November days, none of us saw it and, anyway, they would say that, wouldn't they. Sure, Arkle had been amazing giving away a couple of stone at Leopardstown and Gowran Park, but Mill House had reminded us of his majesty in the King George and the Gainsborough. This was the best horse that Fulke Walwyn had ever trained. John Oaksey had a whole pot of ink at the ready.

Gold Cup day was cold enough for snow showers but there was a trace of wintry sun by Gold Cup time. It was only a four-runner field, but King's Nephew and Pas Seul were pretty good actors for supporting roles. High in the stand, my excitement was doubled as I was changed to ride in the Cathcart at the end of the card.

For a circuit and a half nothing dampened the thought that Mill House was about to give Cheltenham a Gold Cup for the ages. He was regal while Arkle was rank. Ears pricked, white star gleaming, he sailed serenely ahead while Arkle was yawing at the bit with Pat Taaffe at times bolt upright like someone on the losing team of a tug of war.

As they came down the hill towards the ninth, it looked so bad that Peter O'Sullevan said in commentary, "Pat's not having a very happy ride on him at the moment," a remark immediately compounded by Arkle clouting the fence not far above the guard rail.

It was not until they ran up the hill for the final time, the tempo increasing, the others dropped, that Arkle was at the very least a real contender. But it takes a lot to shift a cloak of greatness. Even when Willie Robinson's whip came up as Arkle joined him on the final turn, we believed Mill House would find something to put this usurper away. Arkle jumped a length ahead at the last, but Mill House landed slightly the better and for a moment it looked as if he was closing.

Then he wasn't. He battled on to the line but at the post Arkle was five lengths to the good. There could be no excuses. Mill House galloped on for five more seasons and five gallant victories, including a Whitbread Gold Cup so redolent of lost horizons that grown men cried. But Arkle crushed him in the Hennessy, dismissed him in the Gold Cup, and finally gave him 16lb and a 25-length thrashing at Sandown. The dream had died.

The measure of Arkle's greatness is what he had to overcome that snowy March day in 1964. He brought with him the yearnings of a still struggling nation wanting a champion to call their own and to put it up to their often supercilious bigger neighbour. Arkle delivered all that and more, even enhancing his immortality by the poignancy of his final career-ending defeat.

He did quite wonderful things. He is high in the sporting Valhalla, but the day he first got there was made by the big, white-starred wonder he had to put away. There never was and never will be a race to match it.

'I'd had a month's wages on'

Arkle's groom Johnny Lumley, speaking in 2005, recalls the occasion

I remember the overwhelming tension. It started to build from the moment I arrived at Arkle's box at 8am. From then on, every minute to the race dragged like an hour. After months – it really was months – of banter between the Irish and British, this was crunch time.

Pat Taaffe had convinced me we'd win. I'd had a month's wages on, about £40, at 15-8. But this wasn't a money thing. It was about pride. In the Railway Hotel the night before, a chap of about 16st insisted that even if he rode Mill House they'd beat Arkle.

It was a bitter day with flurries of snow and I was shaking, possibly due more to nerves than the cold, as I prepared Arkle for the race. I fussed over him. He had to look at his best. As I led him up in the paddock, Pat again insisted we'd win.

The course had a different configuration then, and the best place for the groom to watch was down at the final fence. Mill House made the running, tracked by Arkle. Three fences out I saw Willie Robinson go for his whip. My confidence soared. From that point our horse was always travelling the better.

As I led him in, the Irish went crazy with joy. Hats were flying in the air and people didn't bother about catching them. I was walking across a carpet of trilbies. That night I went back to the Railway Hotel – is it there still? – to celebrate. Unfortunately, most of the British who'd been staying there had made their way home. I didn't bother going to bed that night.

Don't miss the rest of this fantastic series here:

Sir Mark Prescott on Mandarin's miracle in the 1962 Grand Steeple-Chase de Paris

Richard Hoiles on Crisp v Red Rum in the 1973 Grand National

Nick Luck on Secretariat's stunning win in the 1973 Belmont Stakes

Jessica Harrington on Grundy v Bustino in the 1975 King George

Chris Cook on Dawn Run's win in the 1986 Cheltenham Gold Cup

Rishi Persad on Dancing Brave's victory in the 1986 Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe

Lee Mottershead on Desert Orchid's win in the 1989 Cheltenham Gold Cup

Richard Forristal on Fantastic Light v Galileo in the 2001 Irish Champion Stakes

Patrick Mullins on Hardy Eustace v Harchibald in the 2005 Champion Hurdle

Stay ahead of the field with 50 per cent off the ultimate racing subscription. Enjoy the Racing Post digital newspaper and award-winning journalism from the best writers in racing. Plus, make informed betting decisions with our expert tips and form study tools. Head to the subscription page and select 'Get Ultimate Monthly', then enter the code WELCOME22 to get 50 per cent off your first three months. First three payments will be charged at £17.48, subscription renews at full monthly price thereafter. Customers wishing to cancel will need to contact us at least seven days before their subscription is due to renew.

Published on inSeries

Last updated

- We believed Dancing Brave could fly - and then he took off to prove it

- 'Don't wind up bookmakers - you might feel clever but your accounts won't last'

- 'There wouldn't be a day I don't think about those boys and their families'

- 'You want a bit of noise, a bit of life - and you have to be fair to punters'

- 'I take flak and it frustrates me - but I'm not going to wreck another horse'

- We believed Dancing Brave could fly - and then he took off to prove it

- 'Don't wind up bookmakers - you might feel clever but your accounts won't last'

- 'There wouldn't be a day I don't think about those boys and their families'

- 'You want a bit of noise, a bit of life - and you have to be fair to punters'

- 'I take flak and it frustrates me - but I'm not going to wreck another horse'