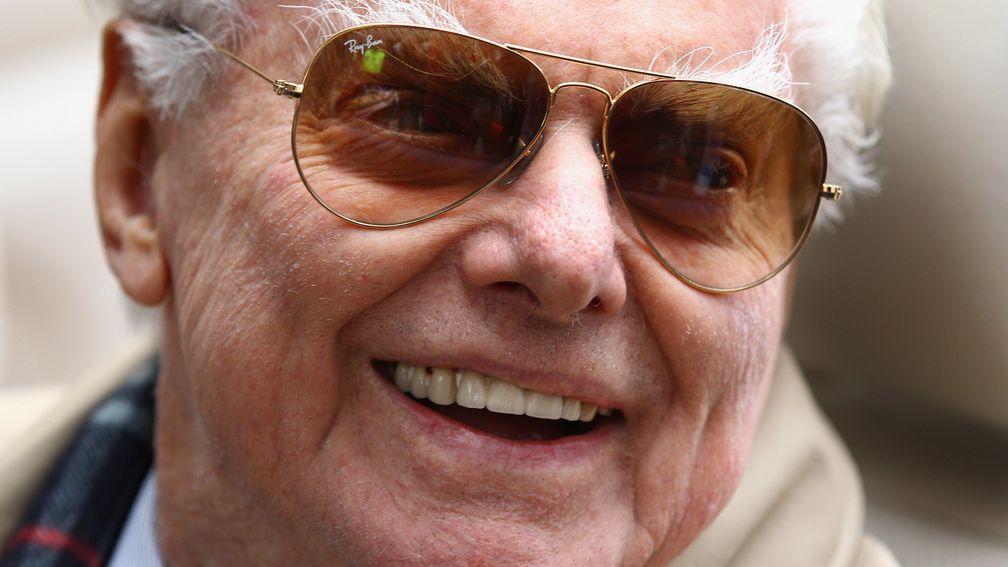

Bart Cummings: the man they call the Cups king

Nicholas Godfrey meets the Australian training legend

First published on Sunday, January 8, 2012

Picture the scene. Bart Cummings, racing legend, is scrutinising the lunch menu at the Terrace, Flemington racecourse's premier restaurant. There's an elegant-looking selection on offer, especially the duck starter, which offers confit pithivier, Peking and parfait with crostini. It is fair to say Cummings is not obviously impressed at the fancy fare.

"What I want is plain duck," says Cummings, bemused and politely exasperated. "I don't know what this means. Can't you give me plain duck?" A few minutes later, the canard duly arrives in a dumpling-style arrangement, accompanied by a slight raising of those famously bushy grey eyebrows before their owner tucks in. "I still don't know what it is," he says quietly, smiling to himself at the absurdity of it all.

Innocuous as it is, the exchange is enlightening. For plain duck, read plain-speaking: one tough cookie, albeit always with a laugh not far away. Bart Cummings is not one for fripperies or fuss, unlikely to suffer fools, never likely to be mistaken for a tall poppy, though he might enjoy cutting down a few.

Be that as it may, if you didn't know you would never guess this impish 84-year-old with the mane of silvergrey hair is the most celebrated figure in the history of Australian racing. Yet here he is, suspiciously eyeing the hors d'oeuvres at a table overlooking the winning post at his second home, three hours before neither of his two representatives come anywhere near adding to his astonishing record of 12 Melbourne Cup victories. Nobody else has won more than five times.

Not content with saddling merely the winner of the 'race that stops a nation', he has trained the first two home on five occasions. That's probably why they've erected a statue in his honour at Flemington.

It is suggested he must feel like he owns the place. "I still have to pay just like everybody else," he shoots back, throwing off any hint of affectation. "I like to treat everything normal, try to keep a low profile," he adds. "It's not working, of course."

For all the trademark humility, Cummings is an icon, one of the greatest trainers the world has ever known. Popular with the racing aficionado and the man on the Moonee Ponds omnibus alike, he maintains an everyman facade. But it isn't every man who has saddled a dozen Melbourne Cup winners, dating back to the filly Light Fingers in 1965 at the height of Beatlemania, when he was 37. After ten more, Cummings' most recent success came 43 years later in 2008, when he was 80 and Beyonce topped the charts. The Fab Four may have long since departed the charts but the 'Cups King' just keeps on going, well into his ninth decade.

CV

Name James Bartholomew Cummings

Born November 14, 1927, in Adelaide, South Australia

Started training May 1953

Main base Leilani Lodge, Randwick, Sydney (also Saintly Place, Flemington, Melbourne)

Big-race wins 264 Group 1s; over 750 stakes victories

First city winner Wells, Morphettville (Adelaide), February 12, 1955

First big win Stormy Passage (1958 South Australia Derby, Morphettville)

Melbourne Cup wins 12 Light Fingers (1965), Galilee (1966), Red Handed (1967), Think Big (1974, 1975), Gold And Black (1977), Hyperno (1979), Kingston Rule (1990), Let’s Elope (1991), Saintly (1996), Rogan Josh (1999), Viewed (2008)

Caulfield Cups 7 Cox Plates 5 (including So You Think 2009, 2010) Golden Slippers 4 AJC Derbys 5 Victoria Derbys 5

So come on Bart, tell us your secret – how do you train a Melbourne Cup winner? "There's no magic formula," he says. "You've got to buy the right horse, you've got to be patient and you've got to feed it right. Good tucker, be kind to it, when it needs a break give it a break - that's about it. It's relentless work and taking an interest in your horse's welfare, and above all plain common sense. If you've got all those things covered, you make your own luck."

In a career spanning nearly 60 years since his first licence in 1953, Cummings has won every Aussie race worth winning, usually on multiple occasions. Often described as racing's answer to Don Bradman, Cummings numbers a record 264 Group 1s among more than 750 stakes winners.

Although the Australian Racehorse of the Year awards began only in 1968-69, by which time Cummings had nearly finished his second decade as a trainer, he was responsible for nine winners of the sport's highest equine accolade. He was the first Australian trainer to top the A$1 million prize-money mark for a single season in 1973-74. When he won the 1989-90 Sydney premiership he became the first trainer to have won city premierships in three states (Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney).

For all that he is one of the most famous men in the racing world, Cummings also has a reputation for being a shy, solitary individual, ill at ease with his celebrity, despite its longevity. "Bart doesn't do interviews," say Australian journalists. Perhaps he makes an exception as he has a new book to promote, an excellent memoir penned by Les Carlyon, doyen of Aussie racing writers.

Why then, has he agreed to another book so soon after the last? "We both need the money," he says. He laughs. It soon transpires you do a lot of laughing when you’re with Cummings, his fondness for the droll one-liner undimmed as he enters his 85th year.

Although friends describe him as a man of warmth and compassion, recent utterances have hinted at a curmudgeonly outlook. In person, such comments – like British racing being “two-bob” – are revealed as pure mischief-making, tongue firmly in cheek. Guarded, he deflects even the most polite enquiry with good-natured humour.

For example, I venture that it is good to see him looking so robust. “It’s good to see you looking so healthy as well,” he grins. We both know it wasn’t me who had a couple of serious health scares the previous year, when Cummings suffered a bout of pneumonia. A stint in hospital meant he was forced to do the unthinkable and miss a significant part of the Melbourne spring carnival.

If the obituaries weren’t being written, the retirement notices were ready for the press. Not, though, as far as Cummings was concerned – and he isn’t keen to dwell on the issue now. “We’re all right now, soon back up and running,” he says.

“I couldn’t wait to get out of hospital,” he adds. “You can’t change the past and you can only influence the future by being positive and doing what you do best. That’s what I’ve done – I’m still up and out every morning.”

Here it should be admitted that the last paragraph is several separate responses shoved together. Cummings said every word, just not in one go: he seldom offers three words where two will do.

If Cummings ever comes close to waxing lyrical, it is when he speaks of his father Jim, whom he credits with starting the Cummings dynasty and teaching him virtually everything he knows. Born of Irish parents who emigrated to South Australia, Jim Cummings spent the early years of the 20th century working for his uncle on an Outback cattle station near Alice Springs. With drought and depression in Australian country districts, his was a hardscrabble existence, enlivened only by riding in match races and then training a few horses of his own, as his son recounts.

What makes him great The foremost trainer in the history of Australian racing, Cummings is a national icon, owing his status chiefly to the race with which his name is synonymous: the Melbourne Cup, which he has won no fewer than 12 times.

The best of times Cummings selects the 1996 Melbourne Cup victory of the homebred Saintly. “I suppose you do get an emotional attachment because he was a homegrown horse who was born at our place,” he says.

The worst of times The end of the 1980s, when the Cups King syndicate venture fell apart. As the recession struck, Cummings was left in the hole for more than As$10m as high-priced yearling purchases left his stable on the cheap in a virtual fire sale. Cummings spent the 1990s repaying the debts.

What you don’t know about him His career was nearly derailed before it started when he was suspended for 12 months after Cilldara won a handicap at Morphettville in November 1961, a week after she had finished last at 50-1. As a boy he suffered from an extreme allergic reaction to horses. A doctor told him to stay away from stables or risk chronic asthma.

“They used to sell horses at that time into the army,” says Cummings. “The horses used to be out in the wild and there was a big market for them to be shipped out to India.

“When father and uncle saw a horse that was probably more thoroughbred than hack they would hide behind a big rock in the gorge and try to lasso ’em, break ’em in and train ’em. That’s how they won the Alice Springs Cup with Myrtle in 1910.”

It’s also how the Cummings dynasty was formed, starting a racing line set to continue for generations to come as Bart and his wife Valmae – married for more than 65 years – have five children, among them the Group 1-winning trainer Anthony. His son James is now employed as foreman at his grandfather’s main Sydney base, Leilani Lodge at Randwick.

From meagre beginnings, Jim Cummings went on to a successful training career after he moved to Adelaide, where his son was brought up surrounded by horses.

“He was a very clever man, a great trainer,” says Cummings. “Dad got to know all about the endurance of horses from his days up there in Alice Springs. You had to learn or you would have perished. I was lucky enough to have all the experience the old bloke picked up and passed on to me. “He was patient, he liked to give horses long steady work with a view to winning a particular race. He was better at that than anyone.” With perhaps one notable exception, that is.

“I’ve been trying to follow his methods ever since. I have always seen myself as applying the lessons he taught me. I dare say it’s working.”

Although Light Fingers is on Cummings’ CV as his first Melbourne Cup winner, in a sense it was his second as he had been his father’s strapper (attendant stable groom) when Comic Court won in 1950. One of his more arduous tasks involved pulling jockey Pat Glennon, who found fame in Europe with Sea-Bird, out of St Kilda nightspots at 2.30am the night before the race. “Talk about trouble – I’d have needed a lasso to keep him out of those places,” he recalls.

Cummings learned from his father the importance of a strict feeding regime to a horse’s wellbeing. “Athletes eat a high-protein diet mainly,” he says, “so if you do that with horses, it should transform them into athletes. That’s my theory and that’s what I focus on. I definitely think that’s an important thing and it probably takes ten weeks or three months to get them at their best.”

Mind you, you’ve got to find the raw material in the first place, which is where Cummings’ annual trip to New Zealand comes into play. He went there for the first time when he was 31 and has been going back ever since, not too long ago locating the horse who became So You Think.

“When I first started I did some research and found that 60 per cent of Group 1 winners came from New Zealand,” he says. “So I thought that’s the place to go and I’ve been going there ever since and had a fair amount of success. Now people are buying horses from Europe – they seem to improve after being here three or four months. If you get them here early enough they could be Group 1 material.”

What, even from a two-bob racing nation? Cummings laughs. “Listen to Mark Johnston, he agrees with me,” he says. “He knows the prize-money’s better in Australia.”

The young Cummings was a pedigree expert in his early days, when he and Valmae used to drive around New Zealand with the back seat of their car full of bloodstock annuals and sales books.

“An ounce of good breeding is worth all the conformation in the world,” he said of 1966 Cup winner Galilee, knock-kneed and pigeon-toed. “Racehorses are bought to win races, not beauty contests.”

An eye for a horse remains important, though. “You can often eliminate horses who are likely to break down if you’ve got an eye for a horse,” he says. “A lot of people used to have it but there aren’t many left.”

And what about a physical specimen? “When you see a champion it’s imprinted on your mind so you’re hoping you can buy one that looks like one.”

So You Think certainly did. “He filled a picture of the perfect horse,” says the trainer, who saddled him to win two Cox Plates. “I bought him for 110 grand – I should have kept some, shouldn’t I?

“He just got better and better,” adds Cummings, before recalling the unlikely circumstances of his first Cox Plate win as an untried three-year-old in 2009. “We were lucky to get him in the race,” he says. “I sat with the raceclub chairman at the Breakfast With The Stars, when they pick the field. I was nice to him and that gave me the advantage to get him in. I think he got a shock when it bloody won!”

Cummings’ disappointment when his old friend and patron, fellow octogenarian Dato Tan Chin Nam, sold a majority share to Coolmore has been well documented and he is on the record criticising trainer, jockey and tactics – anything but the horse himself. Certainly he has no wish to go over old ground, other than to repeat he was shocked when the sale was negotiated while he was in hospital. “I knew nothing about it,” he says. “I wasn’t involved.”

What he said

‘You’re only as old as your horses. Mine are as young as two’

‘Patience is the cheapest thing in racing and the least used’

‘If the Sheikh left England, racing would be closed down in a month – the racing over there isn’t worth two bob’

‘I’ve been asked countless times how much I charge to train a horse. I say to owners: I’ll train it for 50 bucks a day, but if you want to give me a hand, I’ll charge you 75’

What they said about him

‘There may be an equal to Bart somewhere out there but I doubt there is one better’Roy Higgins, who rode Light Fingers and Red Handed to win the Melbourne Cup for Cummings

‘If he took a job as a horse psychologist he would make the horse whisperer look like a novice’Higgins again

‘He takes his work seriously but refuses to take himself seriously’Les Carlyon, doyen of Aussie sportswriters and longtime friend

As for the horse, he is unstinting in his praise. “He was great for Australian racing,” he says. “People felt as if they owned the horse and wanted to go and see him, like they do now with Black Caviar.”

Surprisingly, he is even prepared to compare him to the pantheon of Aussie greats that have gone through his hands. “He’s as good as any of them I’d say. If I had trained him for the Melbourne Cup rather than the Cox Plate first, he probably would have won it. He didn’t have a mileand-a-half race before and I maintain they’ve got to. He was a world champion and never disappointed me.”

Despite that, So You Think isn’t Cummings’ own personal favourite. Even this phlegmatic old-school old-timer, never one to become too attached, has to admit a special fondness for his 1996 Cup winner Saintly, who was home-bred. He had a tear in his eye after the race. “Never had enough on it,” was his excuse, although he now admits it was a more emotional success than the rest.

Saintly’s victory was all the more significant because it came at a time when Cummings could have been forgiven for being at his lowest ebb. He broke Colin Hayes’s prize-money record when his horses won more than A$5m in 1987-88; not long after, a multi-million-dollar syndicate venture fell apart, leaving Cummings holding the baby in the shape of a batch of high-priced yearlings without owners as the recession struck.

“We sorted all that out and never looked back,” he recalls, glossing over the most worrying period of his career, in which he spent the 1990s repaying his debts.

The new century was marked by various honours for a trainer long since regarded as a national treasure. Having been named ABC sportsman of the year in 1975, he received the Order of Australia for services to racing in 1982 and the Centennial medal in 2000. Inducted into the Sport Australia Hall of Fame in 1991, he was an inaugural member of the Racing Hall of Fame ten years later.

He carried the Olympic flame down the Flemington straight in Melbourne when Australia hosted the Olympics in 2000; in 2007, his head appeared on a postage stamp as part of the ‘Australian Legends’ series.

Although Cummings endured the most fallow spell of his enviable career as the big-race winners virtually dried up in the first five years of the century, So You Think put his name back up in lights.

While he hasn’t had a Group 1 winner since that horse’s second Cox Plate win in October 2010, it would take a foolish person to suggest he won’t be playing at the top table again before long. Cummings still has about 70 horses in his care, about the same as usual, split between Sydney and Melbourne. Retirement, it seems, is nowhere in the offing. “What else am I going to do?” he says, sounding incredulous.

Then again, he doesn’t need to do anything else. Cliched as it sounds, they really did break the mould when they made James Bartholomew Cummings.

King of the wisecracks

Bart Cummings is not merely a legend for his training prowess: his wisecracks have also become part of Australian racing folklore. Take an episode at Cummings’ Adelaide stable, when a health inspector was working up courage to approach the trainer.

According to leading Australian sportswriter Les Carlyon, he was “one of life’s little lancecorporals”. Carlyon adds: “He puffs himself up, does a tour of inspection of the stables and yards and marches into the trainer’s office.

“The trainer has been watching him. Bart Cummings lolls back in his chair, an ambush waiting to happen. ‘Mr Cummings,’ the inspector begins, ‘I have to tell you that you have far too many flies in this place.

“‘Well,’ says Bart, ‘tell me exactly how many I should have and I’ll cut ’em down.’”

Then there’s the story about when stable jockey Darren Beadman sensationally quit the saddle at the peak of his career in 1997 to dedicate his life to God and the church. Beadman had ridden both Kingston Rule and Saintly to win the Melbourne Cup for his boss.

When the jockey broke the news to Cummings, himself raised a Catholic, the latter responded: “I think you should get a second opinion.” Later, he added: “As a preacher, he made a very good race jockey.”

Bart Cummings died on August 30, 2015

Members can read the latest exclusive interviews, news analysis and comment available from 6pm daily on racingpost.com

Published on inRP Classics

Last updated