Bribery, chaos, swimming horses and a box of sausages - racing at its wackiest

Lee Mottershead searches near and far for races that are far from the norm

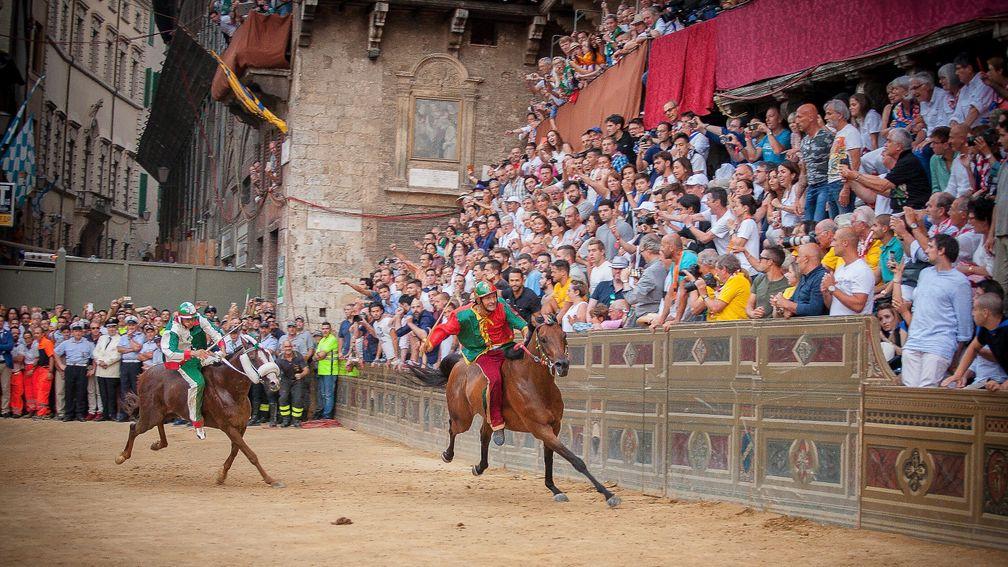

Palio di Siena

It is chaotic, it is madness but to the people of Siena it means more than words could possibly say.

This is no normal horserace, yet it is horseracing in its purest form. Ten randomly-allocated animals, each representing one of the medieval walled city's neighbourhoods (contradas), compete to secure local bragging rights in a frenetic, terrifying and lawless contest covering three 339-metre laps of the Piazza del Campo, Sienna's central square.

Rampant bribery and corruption takes place right up until the point where 60,000 spectators fall silent, awaiting the start of a cultural institution conducted amid cheers, tears and continental exuberance.

The jockeys, each wearing the flamboyant colours of the contrada they represent, use whips made of stretched ox penises to galvanise their mounts and inflict pain on their fellow riders. They whack each other, barge each other and attempt to forge their way to the front.

Preservation of hope is vital - and hope can endure even after horse and human have been parted, for the first horse past the line wins, regardless of whether a jockey is aboard at the time. Had such a rule existed here, Red Rum would have finished only third in the 1977 Grand National.

In the August 2019 Palio a narrow victory went to the nine-year-old Remorex, who had lost Giovanni Atzeni - a cousin of Andrea Atzeni - at the corner where the Cappella di Piazza, an imposing marble chapel, projects out on to the track. It was the Remorex's second riderless triumph in the space of a year.

The Palio has been taking place twice each summer since 1633. Its grip on the people of Sienna remains total. Summing it up, a passionate member of the Giraffa contrada told a BBC documentary: "If the Palio didn't exist, we would have to invent it."

Birdsville Cup

Where the dust never settles. That's how the organisers of Australia's most unusual racing event promote an annual celebration that to devotees needs no promotion.

There is nowhere more remote in Australia than Birdsville, an outback town in Queensland with just 120 residents. For two days and three nights at the start of September the population swells to 8,000. They come from all over the world to witness a Cup like no other, although with the air full of the red dust kicked up by the 12 runners it's hard to witness anything.

In itself it's nothing special, a one-mile handicap whose winning owner receives a typical trophy. What makes it unique is where it is staged, a racecourse in the desert with next to no facilities that can take days or weeks to reach by road. Once there you park your ute by a tree, pitch your tent and hope for the best.

When Australia's famous 60 minutes news programme last year made a film about the Birdsville Cup, presenter Charles Wooley asked regular visitor Fred Brophy - he brings a travelling boxing show to town, as one does - why the Birdsville newcomer was being attacked by a thousand flies but Fred was not.

"Fresh blood," explained Fred.

The thing about the Birdsville Cup is once you've been bitten, you've got the bug.

Alpine Motorenöl Seejagdrennen

The literal translation of the German compound noun 'seejagdrennen' is sea or lake hunting race. This sounds a tad unusual, but so is the contest that provides the standout attraction on the Wednesday evening of Hamburg's Deutsches Derby festival.

Very little jumping now takes place in Germany but a small slice of what remains is made up of lake chases, in which the runners and riders must – well – go through a lake as part of their mutual soggy endeavour.

Bad Harzburg and Quarkenbrück stage lake chases but at both the runners are able to simply gallop through the water.

The finest of all the seejagdrennen is Hamburg's iconic two-and-a-quarter-mile event, in which the lake is so deep the horses must engage in a form of front crawl - or breast girth-stroke - to navigate their way to the other side.

In 2019 the horse leading out of the lake was described by the racecourse commentator as the "bester schwimmer", which requires little in the way of translation.

Less nautically-minded was Sonja Daroszewski's mount, who propelled himself head first into the wet stuff, meaning the poor jockey was left trying to remount in the water. Her perplexed and sodden partner was none other than Box Office, the former JP McManus-owned horse on whom Sir Anthony McCoy retired at Sandown in 2015.

There are, of course, no racecourses that stage lake races in Britain, the nearest equivalent being Ffos Las.

Prix Anjou-Loire Challenge

It was only in 2005 that Le Lion-d'Angers racecourse in France's centre-west created the contest that has come to define it. Not surprisingly, it has gone down a storm.

The Anjou-Loire Challenge is the world's longest horserace, although there is little that is conventional about it.

Across a distance of four and a half miles (plus a little bit more) there are no less than 50 obstacles to be negotiated, including a mound in the corner of the tight circuit that looks more a like a cliff edge with ridges. Early in proceedings horses go hurtling down it but with over four miles already covered they then have to ascend it. Crampons are not essential but probably help.

There are occasions when the field disappears behind a forest, during which time heaven only knows what happens. When visible to a crowd that generally totals around 10,000 locals refreshed by the local wine, the runners and riders take on banks, drops, ditches, water jumps, bullfinches and more besides.

Winning it is a big deal – jockey Clement Lefebvre spent the final 200 metres saluting the packed grandstand. Simply completing the race requires a big effort.

Newmarket Town Plate

It's a long way to go for a box of sausages, particularly as the butcher that makes them has a shop down the road. There is, however, much more to the Newmarket Town Plate than the humble Newmarket banger.

The Plate is the world's oldest horserace, having been founded by King Charles II in 1666 in an act of parliament. Charles, who became the first and only reigning monarch to ride the winner of a horserace in 1671 ("After you, Sire!"), decreed the contest should be run forever, which indeed it has, in most years coinciding with a post-racing concert by Sir Tom Jones.

At three miles and six furlongs, the Plate is a marathon, beginning on National Stud land and staying on it until joining the July course two miles from the finish. The jockeys have to be genuine amateurs and must stick to some of the original rules, one element of which stated: "Every rider that layeth hold on, or striketh, any of the riders, shall win no plate or prize."

Participants have come from all walks of life, with recent winners including trainer John Berry and Sheikh Fahad, who triumphed in 2016 but was then unseated in 2017, albeit without anyone having strikethed him.

As well as the Powters Newmarket Sausages (peppery but balanced by aromatic nutmeg and herbs) the winner receives a perpetual challenge plate, a silver photo frame and a voucher for a Newmarket clothes shop.

Velka Pardubicka

It is the Grand National and then some.

Like the world's most famous steeplechase, the Czech equivalent has been toned down but remains fearsome and unique.

What makes it particularly different is that around a quarter of the four-and-a-quarter-mile race – sometimes referred to as "the devil's race" – is played out not on grass but ploughed field, making an already arduous test even more arduous.

Thankfully not taken from or into a ploughed field is the most iconic fence on the course, the infamous Taxis, jumped only once a year as the fourth obstacle in the Pardubicka and named after racegoer Count Egun Thurn-Taxis, who convinced organisers to keep the fence after riders called for it to be removed. The Count was a talker not a doer.

The fence tends to be approached at great speed – if it was not there would be no chance of getting over the four-metre-long and one-metre-deep ditch that greets horses and riders on the landing side.

Grand National-winning jockey Marcus Armytage once described the Taxis as "the love child of Becher’s Brook and The Chair, on steroids". That sounds about right, although even once that monster has been negotiated those still going have another 27 fences to take.

Pardubice, around 100 kilometres to the east of Prague, is also known for its gingerbread and Semtex. The latter is only marginally more frightening than the town's iconic horserace.

Mongol Derby

When it was said earlier in this feature that the Anjou-Loire Challenge is the world's longest horserace, it should have made clear it is world's longest conventional horserace. Nothing is longer or less conventional than the Mongol Derby.

Over a distance of 1,000 kilometres, it is a Derby for which there are no trials at York or Chester. Inspired by Genghis Khan's pioneering postal service, it requires its daredevil riders to navigate their way across the Mongolian wilderness to each and every one of 25 stations, at which point one pony is replaced by another.

Conditions on the steppe can switch from sweltering heat to monsoon rain to impenetrable fog. That can present a challenge, as can finding somewhere to spend the night. Last year's winner, 70-year-old American Bob Long, found himself knocking on the doors of herdsmen families.

Victory in 2018 went to Oxfordshire's Annabel Neasham, who managed to get from one end of the course to the other in six days and then reflected: "People say when they finish they could easily do another 1,000km. Well, I think I'm good with this."

Grosser Preis von St Moritz

In Switzerland they do all-weather racing a bit differently to Wolverhampton.

On three Sundays in February, at the foot of the 3,123-metre high Piz Rosatsch mountain, a frozen lake in the exclusive ski resort of St Moritz becomes a racecourse for the White Turf races - whose racing looks like nothing staged anywhere else.

For a start it is much whiter, although the winter wonderland scene should no in no way give the impression this is gentle fare. Kickback composed of snowballs and ice has left many a nose bloodied - while punters trying to predict the results on the most singular surface have experienced a similar feeling.

The contests are divided into three sorts, with thoroughbred racing as we know it joined by trotting and ski-jorging, in which the brave souls doing the steering are on skis a metre behind their horses.

The ski-jorging is certainly unusual but probably just outside the confines of what traditional racing fans would constitute to be a horserace, given it involves the introductions of skis and possibly slalom poles as well. Much more of our world is the feature race of the festival, the Grosser Preis, whose 2020 winner, the George Baker-trained Wargrave, went into the event rated a far from shoddy 102.

Should you be keen to acquire a potential Group performer with the ability to not just walk on water but gallop on it, Wargrave is the one.

Bishopscourt Cup

At none of the major festivals is there a race remotely as bad as the KFM Hunters Chase, otherwise known as the Bishopscourt Cup, otherwise known as the farmers' race. It is weird, wacky and more than a little wonderful.

They stage it as the opening contest during the fourth day of the Punchestown Festival, presumably in the hope everyone may have forgotten about it by the time the Grade 1 action begins.

The delight of the Bishopscourt Cup is in its race conditions, which state the two-and-a-half-miler is open only to horses who are, "the bona fide and unconditional property of farmers farming land in the Kildare Hunt District. Sons and daughters of persons qualified to enter, working on their parents' farms and who have no other occupation, are eligible to enter horses".

There is, therefore, a limited pool of eligible participants, while young people who might otherwise have become astronauts, the Taoiseach or starred in Mrs Brown's Boys have instead stayed working on the family farm just to give themselves a shot at local stardom.

In 2012 the invariably hair-raising contest was summed up best by trainer Peter Maher, who spent weeks living off cabbage soup in order to make the weight and face the fearsome test.

"That race is the Cheltenham Gold Cup to us," he said. "Everyone goes too fast and you have loads of fallers, but that's only because all the riders are trying to take the lead so they can get on the telly."

If you enjoyed this you might like the following pieces by Lee Mottershead:

The Guineas: a walkover won by an unnamed jockey sums up the start of Newmarket's Classics

Racing world unites in taking on an eggs-cellent challenge with mixed results

Back in his element: Sir Anthony McCoy is injured again and rather enjoying

'I say it as it is' – a fascinating interview with the incredible Gai Waterhouse

Racing behind closed doors works – and that's just one reason to be cheerful

The plunge from 33-1 to 8-1 that gave Richard Hannon his first winner 50 years ago

What comes next? What will racing look like after the crisis that changed our lives

Attacks on the Cheltenham Festival are easy, lazy and ignore the bigger picture

Who knows when we'll get the Guineas but Japan has a cracker in store next week

Phar Lap takes me back to an Aussie audience with my racing idol

The Derby start is down the road but binoculars are fixed on the cat for now

The split peas refused to soften but Delia's squash and leek soup is a triumph

The big dilemmas facing those tasked with planning the 2020 Flat season

A virtual race but a real triumph on a day when the Grand National won

'I support a resumption wherever and whenever it comes and in whatever form'

Des Lynam: 'At the end of each Grand National I would say: I'm never doing that again!'

How to cope with no Grand National? Wallow in nostalgia and look forward to 2021

It was right to stop British racing but the sport must remain ready to restart

Goshen agony provided the defining moment of a festival full of tight margins

He is not the second coming but with a second festival triumph Samcro is back

The 100-1 Gold Cup winner – how a farmer with three horses masterminded a miracle

'I'm very hopeful – but I'm not sure how much longer I'll be doing my job

How British racing is actually run (and why it sometimes doesn't work)

British racing's power structure and how it can be improved

Kevin Tobin: "I was just staring into a black hole with no clue how to get out"

Richard Dunwoody: no need to pity the man ripped away from a sport he changed

Bookmakers have pledged to donate any profits from betting on the Virtual Grand National to the NHS Charities COVID-19 Urgent Appeal. You can donate to this important cause here

Published on inFeatures

Last updated

- Captain Marvel: how a modern master of Cheltenham and a genuine pioneer executed one of the shocks of the year

- 'We’re delighted with how it's going' - joint-trainers prepare for exciting year after Flat string is doubled

- 'We’ve had to work hard this sales season' - Kennet Valley seeking to build on success with biggest string

- Alastair Down's archives: the great writer recalls Coneygree's glorious victory in the 2015 Cheltenham Gold Cup

- Kauto Star: the extraordinary talent who became the benchmark for sheer undiluted quality

- Captain Marvel: how a modern master of Cheltenham and a genuine pioneer executed one of the shocks of the year

- 'We’re delighted with how it's going' - joint-trainers prepare for exciting year after Flat string is doubled

- 'We’ve had to work hard this sales season' - Kennet Valley seeking to build on success with biggest string

- Alastair Down's archives: the great writer recalls Coneygree's glorious victory in the 2015 Cheltenham Gold Cup

- Kauto Star: the extraordinary talent who became the benchmark for sheer undiluted quality