How other sports can teach us so much about football

Words of wisdom from soccer boffin Kevin Pullein

Before Johan Cruyff became one of the best footballers ever he was a Dutch youth international as a baseball catcher.

He said: “I learned that you had to know where you were going to throw the ball before you received it, which meant that you had to have an idea of all the space around you and where each player was before you made your throw.”

Afterwards he applied the same principle to football. “No football coach ever told me that I had to know were I was going to pass the ball before I had received it, but later on when I was playing football professionally the lessons from baseball – to focus on having a total overview – came back to me.”

You can learn about one sport from another.

Danny Blind won the European Cup playing for Ajax in 1995, just over 20 years after Cruyff had won it with them three times. Blind used to block attackers at corners so they could not run where they wanted to. He said he got the idea watching basketball.

I have learned a lot of things about football and betting from other sports, mostly basketball, and as the 2017-18 NBA season is now underway this seems like a good time to share some of them.

Psychologist Amos Tversky and two of his students, Thomas Gilovich and Robert Vallone, published a paper in 1985 called The Hot Hand in Basketball: On the Misperception of Random Sequences.

More from Kevin Pullein

Assisters contribute just as much as scorers

Defences key in survival battle

A player is said to have a hot hand if his last few throws have gone in the basket. He is said to have a better than usual chance of succeeding with his next throw. Tversky, Gilovich and Vallone said he did not. They sifted through a lot of numbers and found no evidence that players who had been on a good run kept throwing well or that players who had been on a bad run kept throwing poorly.

No one believed them, of course. I trust the numbers. Some recent research, I should add, suggests there might be a tiny hot hand effect after all, but nothing of the magnitude that players, coaches and fans believe in. We tend to remember sequences that carried on and forget the others.

Craig Fox, who had also been one of Tversky’s students, published a paper in 1999 called Strength of Evidence, Judged Probability and Choice Under Uncertainty.

He asked basketball fans to estimate the chance of each team in the NBA playoffs becoming champions. First he asked about one team, then another and so on. Obviously the estimates should add up to 100 per cent. The average total was 240 per cent.

Fox also asked how much people would bet on a team to win $160 if that team became NBA champions. He asked how much they would risk on the first team for the chance to gain $160 and so on. Obviously these answers should add up to less than $160. The average total was $287. We tend to overestimate chances.

Picking Winners Against the Spread is a small, thin book on basketball betting by AJ Friedman. It was published in 1978. There are just 64 pages. I learned more from that book than from any other on how to quantify the ability of sports teams. The ideas in it are simple. Over the years I have developed them many times in many ways but I can still trace them all the way back to their source.

A more complex good book is Basketball on Paper, written in 2004 by Dean Oliver. Its subtitle is Rules and Tools for Performance Analysis.

Oliver noticed several things about basketball that I have noticed about football, which suggests to me that they may occur in other sports too. For example, he discerned a link between passing and scoring. Teams who pass the ball well tend to score more points in basketball just as they tend to score more goals in football.

Oliver also found that for basketball teams good results are more likely to be repeated than bad results. I have found the same with football teams. It is hard to be spectacularly good by accident, much easier to be spectacularly bad. The consequences should encourage everyone.

Oliver also realised that the weaker team in a match benefit when both teams have only a small number of opportunities to score. He advised underdogs who find themselves in the lead to slow down play, taking as long as they are allowed over each possession, which will reduce the number of times in the rest of the match that both teams gain possession.

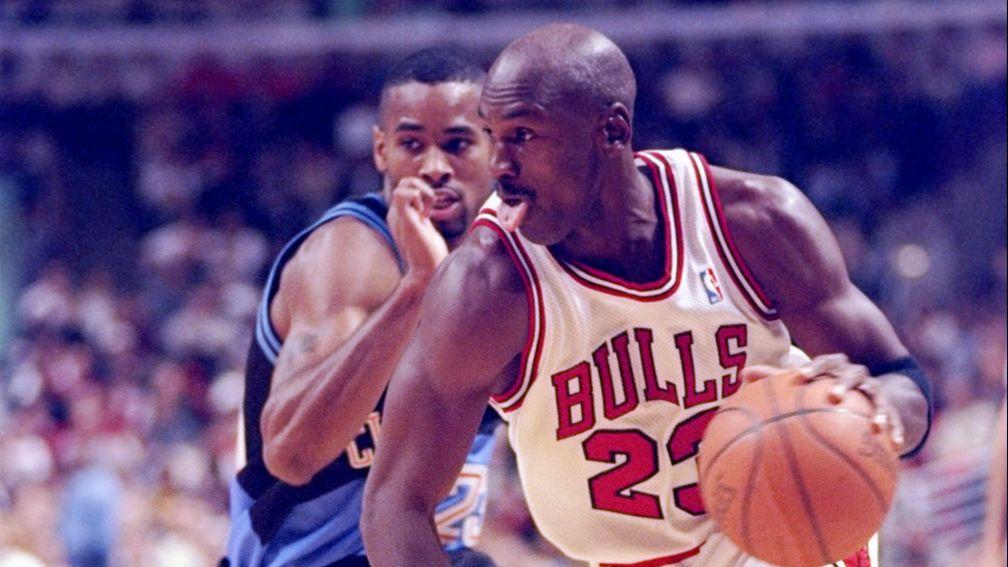

He wrote: “After a game in 1997 in which the turtle-slow Cleveland Cavaliers of Mike Fratello beat the favoured Chicago Bulls 73-70, I estimated that the Cavaliers improved their odds of winning that game from about 28 per cent to 34 per cent by slowing the game from 95 possessions to 78 possessions. Every six per cent matters.”

Consistency is urged on players in all sports, but Oliver recognised that it is desirable only for good ones, not for bad ones. An average performance for a good team will be better than for most of their opponents. If they perform within a narrow range they will maximise the number of performances that should be good enough for a win.

An average performance for a bad team will be worse than for most of their opponents. If they are wildly inconsistent they will be criticised, but they should not worry because by producing a wide range of performances they will increase the number that might enable them to snatch a surprise win. Consistency for a genuinely bad team generates consistently bad results.

In basketball and in other sports.

Today's top sports betting stories

Follow us on Twitter@racingpostsport

Like us on FacebookRacingPostSport

Published on inBruce Millington

Last updated

- Vaccine offers hope that sport will open its doors and is something to celebrate

- DeChambeau's approach doesn't appeal to me, but his price certainly does

- We'd do well to pay greater respect to life's uncertainties

- Bruce Millington: celebrate the range of racing options rather than cutting back

- Villa are clearly on the up but theirs odds oversell the chance of a title miracle

- Vaccine offers hope that sport will open its doors and is something to celebrate

- DeChambeau's approach doesn't appeal to me, but his price certainly does

- We'd do well to pay greater respect to life's uncertainties

- Bruce Millington: celebrate the range of racing options rather than cutting back

- Villa are clearly on the up but theirs odds oversell the chance of a title miracle