Bloodstock figures go public with claims of malpractice in the sales ring

The spotlight is on the sales ring after the BHA this week revealed it is reviewing how horses are bought and sold in Britain amid allegations of criminal malpractice. Few and far between are the industry insiders who go public on their concerns about the ethics of the sector, but Lee Mottershead has spoken to two who believe current regulations and practices fall a long way short of being good enough

The sales companies say there is no cause for alarm. The BHA wants to know if such confidence is merited.

Auction houses argue if people are unhappy about practices linked to the buying and selling of horses in the ring, complaints are not being made to them. Yet some people are complaining. Most have done so anonymously. Until now.

The BHA this week confirmed it is reviewing the buying and selling of bloodstock, together with the industry's code of practice, having become "concerned about evidence of unsatisfactory experiences for owners and prospective owners".

The Racing Post contacted a number of industry professionals, both before and after the BHA's Tuesday statement. Many echoed the view there was no reason for the governing body to become involved. Others have welcomed the intervention.

Concerns have been expressed not simply by those buying horses but also those selling them.

In particular, some vendors say they have become frustrated at feeling compelled to make a post-sale payment, known as luck money, to the individual buying their horse or, more regularly, the agent or trainer representing the buyer.

Within the code of practice it is made clear payment of luck money should be entirely voluntary. Bruised vendors now say there is all too often nothing voluntary about the arrangement, with a number reporting agents have told them they will not consider buying a horse without a luck-money promise.

Some industry insiders state this is merely the tip of an iceberg.

An unsafe environment

Philippa Cooper is no stranger to the sales ring. During Book 1 of last year's Tattersalls October Yearling Sale her Normandie Stud sold Dubawi colt Glorious Journey to Godolphin for 2,600,000gns. She has bred a host of high-class racehorses but says she has suffered some unpleasant experiences when attempting to sell them.

"I feel, personally, I am in an unsafe environment at the sales," says Cooper. "They have a code of practice but it is broken and not policed."

She explains: "I first attended a bloodstock sale in 1997. I had my heart set on a certain filly. However, the vendor, when he heard of my interest, which in my naivety I declared, warned me off bidding for her, saying she was intended for somebody else.

"I questioned this. He said if I was intent on proceeding he would run me up to an unattainable price. Unfortunately, I was so angry at him that I bid against him. He did exactly what he said he would do. I ended up with the filly and, 20 years on, she is in my paddock, having never raced.

"In 1999 I went to the sales with two filly yearlings. I was approached with offers from sundry people, the worst one being he had a client who was willing to pay £250,000 for her, and if I was happy with £150,000 I should split the £100,000 difference with him."

That happened in 1999. Bloodstock figures on both the buying and selling side are adamant such activity, which could in some circumstances be deemed criminal, continues.

"It is totally fraudulent," said one, who spoke of agents being known for seeking a "split the difference" arrangement with vendors, similar to the one Cooper highlights. It is claimed owners based overseas have been particularly hard hit, although without ever realising they have been defrauded.

Another allegation has been individuals have bought horses for clients they themselves were selling, but not in their own name.

Lucky for some

The latest updated form of the bloodstock industry code of practice, which came into force in January, 2009, contains guidance on the subject of luck money.

It reads: "An agent shall disclose to his principal and, if required, account to his principal for any luck money paid to him by or on behalf of a vendor…

"The practice of giving and receiving luck money shall be entirely voluntary, transparent and should be disclosed to all appropriate parties by the recipient. A vendor has no obligation whatsoever to pay luck money and the non-payment of such should not prejudice any further business activity."

To those outside racing and bloodstock, it may seem odd someone selling a horse should make a financial payment to the individual buying a horse, or more commonly to that person's agent. The practice has also been synonymous with agricultural sales, although it is dying out, while the sums involved are typically in the region of just £20.

Sotheby's has confirmed to the Racing Post such payments are not allowed in connection to any of its auctions. Conversely, these payments have become ingrained in the sphere of bloodstock sales, to the extent vendors claim certain buyers will, in the main, shun the horses of those consignors who do not see it is as their duty to pay.

One breeder told the Racing Post: "It's a big problem but I can't be named saying that. I might as well give up the game if I do.

"It is absolutely rife. Everyone has to play the game. If you don't give it they don't buy from you again, unless you have a very special horse. My estimate is most vendors pay luck money because they have to pay it."

Cooper says: "It is common practice some agents and a few trainers would expect the vendor to pay them five per cent, which is euphemistically called luck money – lucky for them but not for the vendor, who has to pay five per cent to the sales company amongst other deductions.

"I have been threatened by one trainer that if I didn’t give him luck money, he would make sure nobody ever bought from me again."

She adds: "It is the smaller breeder I feel most sorry for. When there are another 30 or 40 yearlings by the same stallion, how do they get their horse sold without some kind of payback being suggested to them?

"It is they who suffer the intimidation. I have removed myself from that scenario, but I know what it feels like, and it shouldn’t go on."

Another experienced breeder put on a faux-shocked expression when asked if luck money is demanded by agents, who inevitably can already increase their own commissions the more they pay for a horse.

"Really!" the breeder said, before adding: "It has always happened. The difference is now it is more brazen."

The price is right – but wrong

In addition to the allegation that agents on occasions conspire with vendors to inflate the price of a horse in order to split proceeds over the real sale price, insiders also claim some vendors, or others with an interest, actively 'run up' prices by directly, or with a 'stand-in', bidding in the ring against genuine prospective purchasers.

This is, in part, possible because vendors, perfectly legally, can bid to buy their horses beyond any submitted reserve price.

Sotheby's does not permit this, with a spokesperson saying: "Consignment agreements state the seller will not bid on their own property or get a third party to bid on their behalf. This is strictly enforced."

Thoroughbred Breeders' Association board member Bryan Mayoh, breeder of Gold Cup hero Sizing John, buys broodmares and sells their produce.

He says: "It is my opinion the protocols used by both of the major bloodstock auction houses have weaknesses that make the simple concept of buying a horse at auction far more intimidating to prospective buyers than it ought to be.

"The result is that when the BHA and HRI are trying hard to get new owners into racing, a prospective owner visiting an auction for the first time might well wonder what on earth he is getting into.

"Firstly, the vendor normally sets a reserve but this is not announced or shown on the board. Up to the level of the reserve the auctioneer might well take bids 'off the wall', so the price rises via some mysterious bidding process invisible to the untrained eye.

"Even when the reserve is reached, the vendor can place bids on his own horse, aiming to 'run up' the genuine would-be buyer even though the reserve should surely reflect his real view of the horse's value. This is not only allowed by the auction house, it is practically encouraged.

"A vendor buy-back incurs 2.5 per cent commission, so it seems a pretty bad deal for the sales company when a vendor outbids a genuine buyer.

"However, if vendors win out more times than not in the game of bluff, and end up as underbidders on their own horses, both they and the sales company win - but they win at the expense of leaving a very sour taste in the mouth of the buyer if he finds out what has gone on."

Mayoh only bids if told a reserve in advance. That sometimes is not enough.

"At one sale last year I twice talked to the vendor of a mare and ascertained the reserve," he says. "Twice I bid the reserve price but stopped soon after because this equated to my own valuation. Twice I was outbid by the vendor, who had said not a word about his intention to 'support' or 'buy back' or whatever euphemism you choose.

"The result? I wasted my time. I missed out on bidding on horses earlier in the auction whilst waiting for ones whose 'reserves' proved to be false. There are also now two vendors whose horses I shall never look at again.

"Moving to a more open and transparent auction process, with the sales companies encouraging this by revealing the reserve and banning vendor buybacks (or at least discouraging them by charging full commission), even if they do maintain their addiction to 'off the wall' bidding below the reserve price, would help to create an auction environment that is far more customer-friendly, which is ultimately the best way to get more customers and grow your industry."

Cooper does go public on her reserve levels. Last year that almost cost her dear.

She says: "Vendors should not be allowed to run up nor bid on their horses and reserves should be declared, but not false reserves, which is often the case. I am scrupulous about declaring my reserves, but people don’t really believe you.

"Glorious Journey was stuck on £650,000 for 30 seconds. Nobody believed it was the reserve and they couldn’t understand why nobody was bidding. A vendor would often use somebody to run up the horse in those circumstances. The hammer was about to go down, and then people sprang into action. I could have lost out for being so up front."

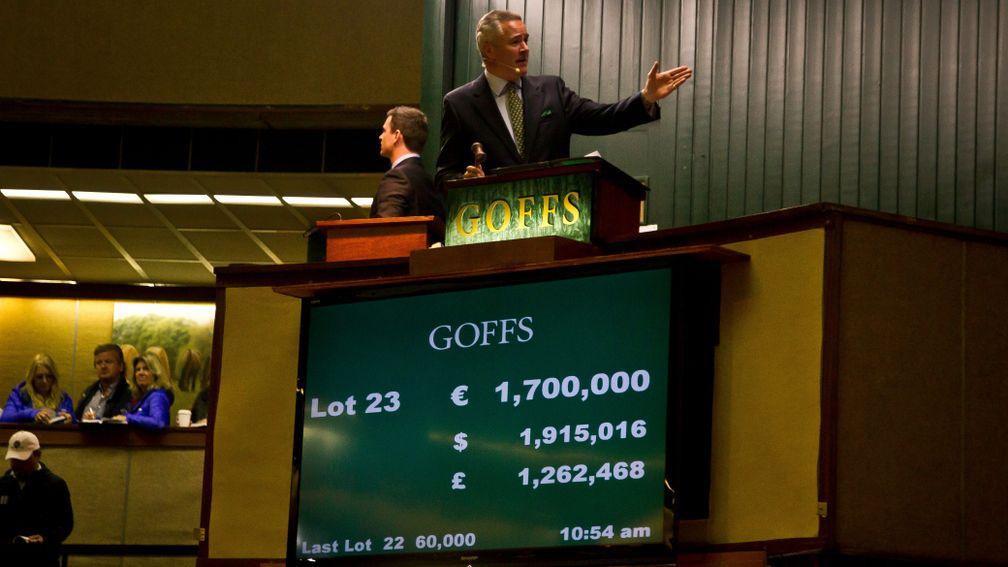

Goffs group chief executive Henry Beeby points out the Sale of Goods Act enables vendors to bid and does not see a problem with the practice.

"I don't think there's anything wrong or unfair in it," he says. "If a purchaser likes a horse he must value it himself. We always say to people they should work out what a horse is worth and then bid up to that figure. Nobody is making anybody bid."

We can't help if you don't talk to us

Both Tattersalls and Goffs mount a strong defence of the propriety of their sales.

Tattersalls' marketing director Jimmy George stresses integrity is "a priority" and pledges the company will "work with all parties to ensure we continue to set the highest possible standards".

Goffs echo those comments.

"I am adamant British and Irish bloodstock auctions are as fair and transparent as they can possibly be," says Beeby.

"We watch everything that happens. There are also codes of conduct in place. Since they were introduced, and even beforehand, we've never had any vendor, purchaser or person make a complaint. We trade on our integrity and I trade on mine.

"I don't know what is said in private conversations any more than anyone else does. My concern is one man's perception is another man's reality. I slightly worry some people think they know what's going on when, in reality, it isn't going on."

Beeby highlights that in the past vendors could go to the office of an auction house and draw out large sums of cash after a sale. This was stopped as it was deemed to be subtly encouraging the payment of money from one party to another. He points to the change of policy as evidence of policing the arena.

Beeby is also exasperated by the silence of those who talk about wrongdoing being rife but refuse to speak publicly or make formal protestations.

He says: "If you were caught drink driving 25 years ago, people would have said it was a bit of bad luck. Nowadays if you tell someone you've been done for drink driving you'll be told it's a disgraceful thing to have done.

"Maybe what's needed here is a similar change of attitude? Talking off the record to a journalist is one thing, and in a way it's commendable, but will it solve the problem?

"It's frustrating for me if people feel there is a problem with the auction process but won't say anything. It's like walking by as someone is being beaten up in the street because you don't want to get involved."

Beeby adds: "If there is a bad apple – and maybe there's one in every barrel – I would suggest to anyone with concerns that if enough people say something about that particular person then surely public opinion will turn against him or her.

"If nobody is prepared to stand up, how is anything ever going to change? If there are people, and to me it's a big if, who are behaving in an unacceptable way, how many people have to walk on by? I can't help people if they don't come and tell us."

COMMENT

Blurred moral lines make case for review incontrovertible

It is easy to sympathise with auction houses saying they can only take action if complaints are lodged. It is also true evidence presented by those who allege wrongdoing in the ring is largely anecdotal. There is, nonetheless, good reason for that.

Those vendors being adversely affected have been afraid to report malpractice to sales companies or the BHA. Breeders need to be able to sell their horses. To do that they require a pool of people prepared to buy them. They feel there is a danger associated with alienating those people.

At the very least it is absolutely right the BHA has started a review.

The regulatory remit of British racing's governing body does not extend to the sales ring but it can influence what goes on there. It can also take action against those behaving badly by warning them off licensed property, such as racecourses and stables. That would also make it an offence for licensed individuals to have professional dealings with them. As such, the BHA does have power.

The sales companies are proud of their transparency. They could be even more transparent by making clear not just who consigns every horse but by stating, in full detail, who owns those horses, including part-ownership and foal share arrangements.

There is also a powerful case for stopping, or strongly discouraging, the unsatisfactory peculiarity of vendors bidding beyond reserves. Henry Beeby is correct to argue buyers must put their own valuation on a horse. So, too, must vendors. They do that through setting a reserve. This surely ought to be sufficient in most circumstances.

There is definitely no reason why any buyer, trainer or agent should feel justified in demanding, or being in any way entitled to, a financial 'reward' from vendors, especially if he or she is already being paid by the buyer. This is not the same as Tesco thanking customers with Clubcard points.

Is all luck money declared to the person for whom the agent is working? Moreover, is it fully declared to HMRC or the Irish Revenue? If it is not, the BHA may be correct in its suspicion some bloodstock practices stray into criminal territory.

If a revised code of practice continues to recognise and approve luck money, the system should be changed so it is part of the terms of sale that both parties declare to the auction house all sums paid with the amounts properly documented.

The sales arena is frequented by a host of honourable people, whose reputation need not be tarnished by the BHA's review.

One can, however, contend that a failing of the bloodstock sales sector, and what occurs within it, is that much of what to most outsiders would immediately be seen as wholly inappropriate is seldom questioned by some insiders.

Moral lines are blurred. If this review can bring greater clarity to what is right and what is wrong, the industry, together with those who work and play in it, will be the beneficiaries.

Lee Mottershead

If you found this interesting, you might like to read...

BHA to review bloodstock sales amid ethical concernsOwners' chief urges buyers to keep sense of proportionTBA says breeders need to be confident when selling at auction

Members can read the latest exclusive interviews, news analysis and comment available from 6pm daily on racingpost.com

Published on inNews

Last updated

- Join Racing Post Members' Club for the very best in racing journalism - including Patrick Mullins' unmissable trip to see Gordon Elliott

- Join the same team as Ryan Moore, Harry Cobden and other top jockeys with 50% off Racing Post Members' Club

- Racing Post Members' Club: 50% off your first three months

- 'It’s really exciting we can connect Wentworth's story to Stubbs' - last chance to catch master painter's homecoming

- The jumps season is getting into full swing - and now is the perfect time to join Racing Post Members' Club with 50% off

- Join Racing Post Members' Club for the very best in racing journalism - including Patrick Mullins' unmissable trip to see Gordon Elliott

- Join the same team as Ryan Moore, Harry Cobden and other top jockeys with 50% off Racing Post Members' Club

- Racing Post Members' Club: 50% off your first three months

- 'It’s really exciting we can connect Wentworth's story to Stubbs' - last chance to catch master painter's homecoming

- The jumps season is getting into full swing - and now is the perfect time to join Racing Post Members' Club with 50% off