A passion for racing that kept pace with momentous change

Julian Muscat reflects on how shifts in the sport affected the Queen

The Queen's adoption of horseracing as her favourite pastime reached its 80th anniversary in May 2022. It was in 1942 that she had visited the stables of Fred Darling at Beckhampton, where Roger and Harry Charlton now train. Needless to say, she would have encountered a very different vista to the one prevailing today.

The most obvious contrast back then was that Britain was heavily embroiled in World War II. Germany was at the height of its military might when Princess Elizabeth, then 16, accompanied her father, George VI, to run her eye over two horses who had done the king proud.

Big Game and Sun Chariot were the sources of her curiosity. They had just won the 2,000 Guineas and 1,000 Guineas respectively and were strongly fancied to follow up in the wartime Derby and Oaks, which were run at Newmarket. In the event Big Game was beaten for the only time in nine outings, but Sun Chariot landed the Oaks despite blowing the start, in the process forfeiting considerable ground.

The young princess would not have seen either of those races. It would be another six years before the BBC started broadcasting live racing, starting on the Flat with the 1946 Lincoln, which attracted a record field of 58 runners in an old-fashioned cavalry charge. Today's Grand National would look tame by comparison.

Another fundamental visual difference in Sun Chariot's Oaks was that starting stalls were even more distant a prospect than live racing on television. They weren't introduced on British racecourses until 1965, and only then to a storm of protest from many trainers.

In those days Flat races were begun by flag from a standing start. Getting away quickly was an art, and none was better at poaching an early advantage than Gordon Richards.

However, the saddle skills that would earn Richards 26 champion jockey titles were rendered impotent by Sun Chariot's contrary nature.

To describe Sun Chariot as temperamental would be charitable. She was prone to falling to her knees and roaring like an enraged bull, which she'd done when Princess Elizabeth had visited her with her father at Beckhampton the previous month. She behaved just as badly before the Oaks. Some accounts have her losing more than 100 yards through her mulishness, yet she still scythed through the field.

Fast-forward four years and the tape start almost did for another of George VI's fillies in a Classic: this time Hypericum in the 1946 1,000 Guineas. Hypericum shed her jockey at the start and was finally caught in the Rowley Mile car park. She delayed the race by more than 15 minutes – an unthinkable proposition today – but was returned to the start and duly won.

Princess Elizabeth was at Newmarket to witness it in person. By all accounts she was intrigued by Hypericum's haughty antics, especially when she tried to decant her jockey a second time just before the tapes rose.

Her Majesty ascended to the throne on the death of George VI in 1952. The following year, just four days after her coronation, she was at Epsom to watch Aureole, her first Derby runner in the royal silks. The infield heaved with more than 150,000 spectators, in sharp contrast to the sparser gatherings on the Downs today.

On that day the Queen would have been much more visible, since the paddock was sited some 200 yards beyond Epsom's winning post. With the paddock repositioned behind the grandstand, she would have taken only a handful of steps to it on her last visit to Epsom. In bygone days she would have walked down to the old paddock, waving merrily to her subjects as she went. In the event Aureole ran well but was no match for Pinza, who gave Richards his first, and only, Derby winner at the 28th attempt.

The 1950s saw French-trained horses run riot over the British turf. Alec Head, Joseph Lieux, Francois Mathet, Charles Semblat and Sea-Bird's trainer Etienne Pollet all won more than one Classic, while French horses headed by Montaval filled the first four places in the 1957 King George VI & Queen Elizabeth Stakes.

Perhaps this swarm of cross-Channel invaders is what prompted the Queen to say that but for her Archbishop of Canterbury she would fly to Longchamp every Sunday to watch racing. Yet within this period of French dominance the Queen celebrated her first Classic winner when the Lester Piggott-ridden Carrozza landed the Oaks in 1957. Carrozza was the lesser-fancied royal runner behind Mulberry Harbour, who finished ninth.

A less savoury aspect of racing in Britain in that decade was the spectre of doping which, if not rife, was certainly prevalent. One victim of the nobblers was almost certainly Alcide. The colt was withdrawn one week before the 1958 Derby, for which he was a red-hot favourite, after he'd worked like a selling plater. Alcide duly rebounded to win the St Leger by eight lengths.

The 1950s was something of a golden decade for the royal horses. It closed with a Royal Ascot double in 1959, courtesy of Pindari (King Edward VII Stakes) and Above Suspicion (St James's Palace Stakes), which took Her Majesty's Royal Ascot haul to 11 in seven years. It would not last. Just two further winners at the royal meeting were recorded throughout the 1960s, when the prowess of the Irish duo Vincent O'Brien and Paddy Prendergast was increasingly felt on the British turf.

At that time the racing scene was dominated by up to 20 owner-breeders of similar size to the Royal Studs. They owned up to 30 mares each and kept around 40 horses in training annually. The two exceptions were the Aga Khan and the French industrialist Marcel Boussac, who both had around twice as many mares and achieved periods of dominance in consequence.

Indeed, Only For Life was the sole British-trained winner of a Classic in 1963, when France’s brace in the Derby (Relko) and 2,000 Guineas (Hula Dancer) was matched by Prendergast, who landed the Oaks (Noblesse) and St Leger (Ragusa) for Ireland. Ragusa's King George triumph, together with that of Khalkis in the Eclipse, ensured that Prendergast became champion trainer in Britain.

The struggles of British owner-breeders to compete at the highest level throughout the decade were emphasised in 1966 when Charlottown became the first British-trained Derby winner in five years. And in that year, had the Queen wanted to train horses under her own name, she would have been able to do so after the Jockey Club finally allowed women to take out a trainer's licence.

The Royal Studs, which fared poorly in the 1960s, rebounded with gusto the following decade. The Queen won four Classics with Highclere (1974 1,000 Guineas and Prix de Diane) and Dunfermline, who landed the Oaks and St Leger in the Silver Jubilee year of 1977.

Highclere and Dunfermline were of a type. Bred by the Royal Studs, they were prime produce of the breeding scene in Europe. Dunfermline in particular was stoutly bred, as was the vogue then. Both of her grandfathers, Ballymoss and St Paddy, were also winners of the St Leger.

However, throughout the 1970s a more precocious type of racehorse was being bred in the US. It was cast from a fusion of former European runners and fast, hardy racemares, and it would make a huge impact in Britain.

From 1970 five of the next eight Derby winners – Nijinsky, Mill Reef, Roberto, Empery and The Minstrel – were bred in the US. And when all except Mill Reef returned to the land of their birth to take up stallion duties, they blended so well with indigenous bloodlines that their progeny took the thoroughbred into a new domain.

The Royal Studs were slow to embrace this breed-changing dynamic, and when they did, the results were disappointing.

It was Robert Sangster who capitalised best after committing vast sums that were beyond the reach of British owner-breeders. In the space of a few years, Sangster's input saw the industry morph from a hobby into big business.

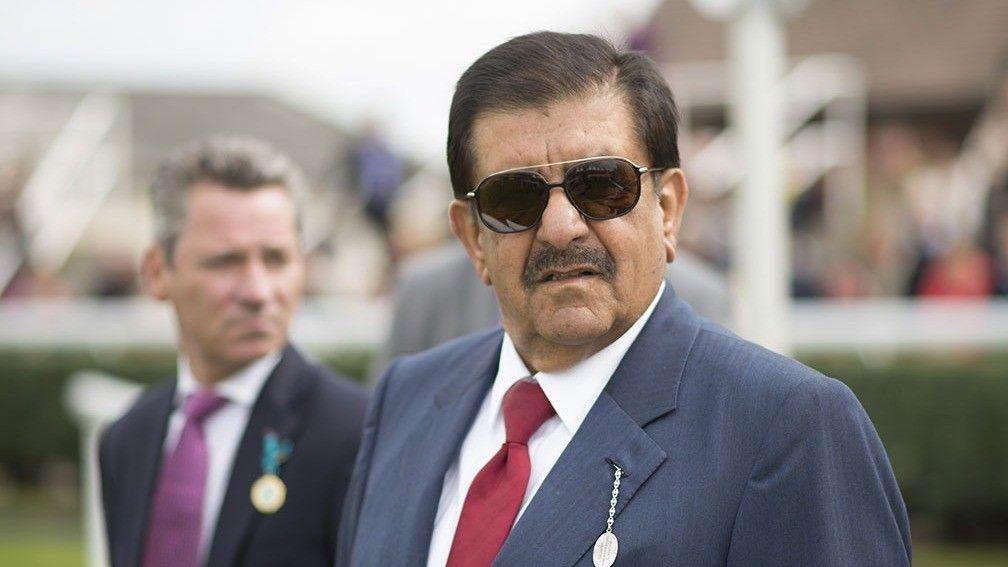

Remarkably, Sangster's hegemony would endure for just a decade. In the summer of 1977, three weeks after his colt The Minstrel won the Derby, a man from the Middle East took a train to Brighton to watch his first racehorse, Hatta, win a two-year-old maiden.

From that low-key introduction, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum's embrace of the sport would soon grow to a level never previously seen anywhere in the world. It wasn't just by numbers alone: each of his young horses descended from the finest bloodlines. And there were hundreds of them every year. The Queen was not alone in being unable to compete.

What's more, Sheikh Mohammed wasn't an isolated case. His brothers, Sheikh Maktoum and Sheikh Hamdan, established sizeable breeding entities alongside other Middle Eastern royals and potentates like Khalid Abdullah. It was an influx on an unprecedented scale.

In the circumstances it wasn't surprising 36 years elapsed between Dunfermline's St Leger triumph and the Queen's next Group 1 winner in Britain: Estimate's Gold Cup victory in 2013. By then she stood virtually alone among old-school British owner-breeders. Others were simply swept away by the combination of resources required to compete and the competitiveness of racing in Britain as a consequence of the Middle Eastern influence.

One filly who might have made a difference was the royal homebred daughter of Highclere, Height Of Fashion. A two-year-old in 1981, Height Of Fashion won all three of her starts to earn the accolade of champion two-year-old filly. She then won her first two starts the following season, after which she was sold to Sheikh Hamdan.

At the time her sale seemed opportune, since Height Of Fashion ran twice more for the sheikh and was barely sighted. How misplaced that supposition was to prove. Height Of Fashion's first two foals, Alwasmi and Unfuwain, both won Group races, but the third was of an entirely different hue. Victories in the 2,000 Guineas, Derby, Eclipse and King George in 1989 placed Nashwan among the best horses of the 20th century.

Sheikh Hamdan had hit the jackpot, especially when some of Height Of Fashion's daughters threw a slew of superior horses – among them Ghanaati, winner of the 2009 Coronation Stakes and 1,000 Guineas. And the sorry episode was compounded by criticism directed at the Queen's racing manager Lord Carnarvon, who'd given trainer Dick Hern notice to quit Her Majesty's West Ilsley stables – which she'd bought with the proceeds from Height Of Fashion's sale – on health grounds in 1988.

Would the Queen have got as much from Height Of Fashion had the filly not been sold? We will never know the answer to that question, except that the episode was indicative of the difficulties she faced in competing against the Middle Eastern petrodollar. She was far from alone in selling choice produce at a time when bloodstock values went through the roof.

Sheikh Hamdan spared no expense on Height Of Fashion's mates at stud, all of which were based in North America. She opened her innings with successive visits to Northern Dancer, whose covering fee at the time stood at $500,000 – and would soon rise to $1 million. Her union with Blushing Groom, which produced Nashwan, came when that sire stood at $275,000. Then followed visits to the likes of Mr Prospector (three times), Danzig, Gulch, Lyphard and Riverman, all of which stood at substantial six-figure sums.

It is inconceivable the Queen could have made a similar financial commitment to Height Of Fashion, whose rugged bloodlines benefited from infusions with the finest stallions in Kentucky. And when it came to her own mares, the Queen was compromised in her choice of stallion by the political unrest in Ireland during the Troubles.

For three decades from the early 1970s, sending royal mares to stallions based in Ireland, where so many of the finest stood, was deemed an unacceptable security risk. The success of the Royal Studs suffered in tandem.

Undaunted, the Queen raised her game in her later years, investing in new broodmares and patronising top-end stallions in Ireland and elsewhere in the quest to revive her racing fortunes. That quest bore fruit in 2021 when she had 36 winners, her best ever total as an owner.

It may not have compared to the heady days when Her Majesty won Classics, but then, the world of racing is a very different one today.

Click here for a detailed look at the Queen's achievements in racing

In Tuesday's Racing Post

Published on inNews

Last updated

- Join Racing Post Members' Club for the very best in racing journalism - including Patrick Mullins' unmissable trip to see Gordon Elliott

- Join the same team as Ryan Moore, Harry Cobden and other top jockeys with 50% off Racing Post Members' Club

- Racing Post Members' Club: 50% off your first three months

- 'It’s really exciting we can connect Wentworth's story to Stubbs' - last chance to catch master painter's homecoming

- The jumps season is getting into full swing - and now is the perfect time to join Racing Post Members' Club with 50% off

- Join Racing Post Members' Club for the very best in racing journalism - including Patrick Mullins' unmissable trip to see Gordon Elliott

- Join the same team as Ryan Moore, Harry Cobden and other top jockeys with 50% off Racing Post Members' Club

- Racing Post Members' Club: 50% off your first three months

- 'It’s really exciting we can connect Wentworth's story to Stubbs' - last chance to catch master painter's homecoming

- The jumps season is getting into full swing - and now is the perfect time to join Racing Post Members' Club with 50% off