The herdsman's lore that produced consecutive winners of the Kentucky Derby

Chris McGrath meets the man who raised both Nyquist and Always Dreaming

When Gerry Dilger arrived in the Bluegrass, he found himself among only a handful of Irishmen. He recites the names. "There were maybe only five or six of us in the old times," he says. "Gerry O'Meara. David Mullins who passed away. Robbie Lyons. Ger O'Brien. And Richard Barry, of course, at Ashford."

Now you go into McCarthy's bar in Lexington, on a music night, and see the latest tide of the diaspora, a circle of dancers opening and closing round the song: pale, open-faced youths, pointing their toes and hoisting their knees, shyly smiling in nostalgia for a childhood only short years ago.

To be fair, Dilger himself sounds as though he cannot have been here any longer than the youngest of them. "People ask if I'm visiting," he admits. "And I say no, I'm living here. Oh very good; and since when are you here? Since 38 years."

Doyen

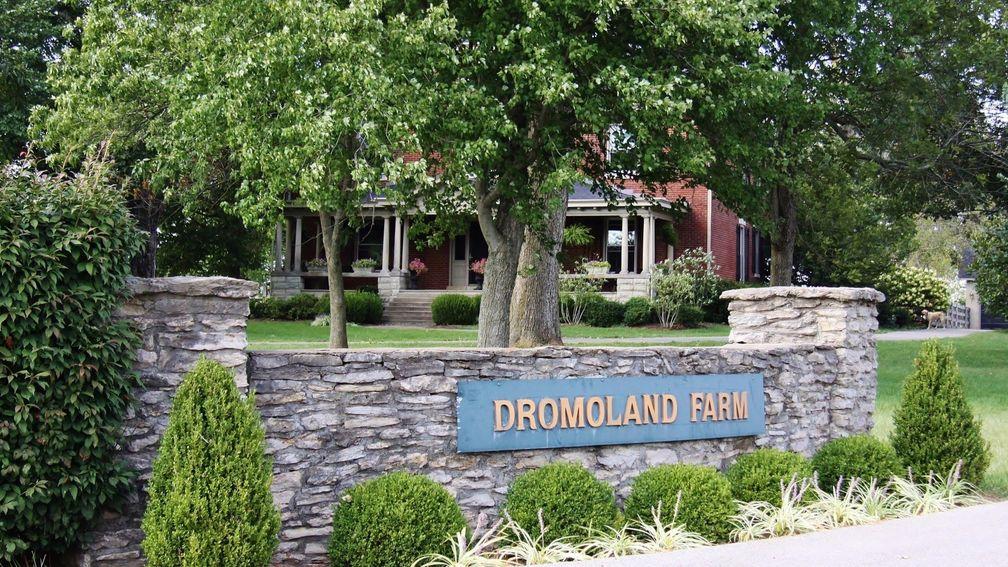

Thirty-eight years, plus a Chicago wife and three Irish-American kids, since the day at Shannon airport when he felt like "taking two steps backward for every one forward down that runway." Certainly he had no intention of staying beyond six months. Yet now he is pointed out to newcomers as the doyen of their calling, a pathfinder of the old school for Irish horsemen - his status consummated, in barely credible fashion, by the fact that the last two Kentucky Derby winners both graduated from his Dromoland Farm nursery. From an annual crop of 20,000 thoroughbreds foaled in North America, first Nyquist and then Always Dreaming figured among the 40 or so that pass annually through his hands.

He disowns the obvious implication. "I'm no better than the man next door," he says firmly. "I got lucky. Put it down to hard work, whatever, but I got lucky. I'm no better than any of my buddies in town here."

Be that as it may, the one certainty is that over the years a latent genius of some kind has been drawn out from somewhere. Dilger had no immediate roots in stockmanship, beyond hanging round the cattle mart in Ennis as a boy. Yet he has a brother alongside on the farm, and a cousin also working with horses in Mullingar. He speculates that a German forbear, a few generations back, must have exported a genetic knack for horsemanship. Otherwise there is just the lore he absorbed as a young man, after completing the Irish National Stud foundation in 1977; above all, when coming under the beady-eyed guidance of Tony Butler at Brownstown.

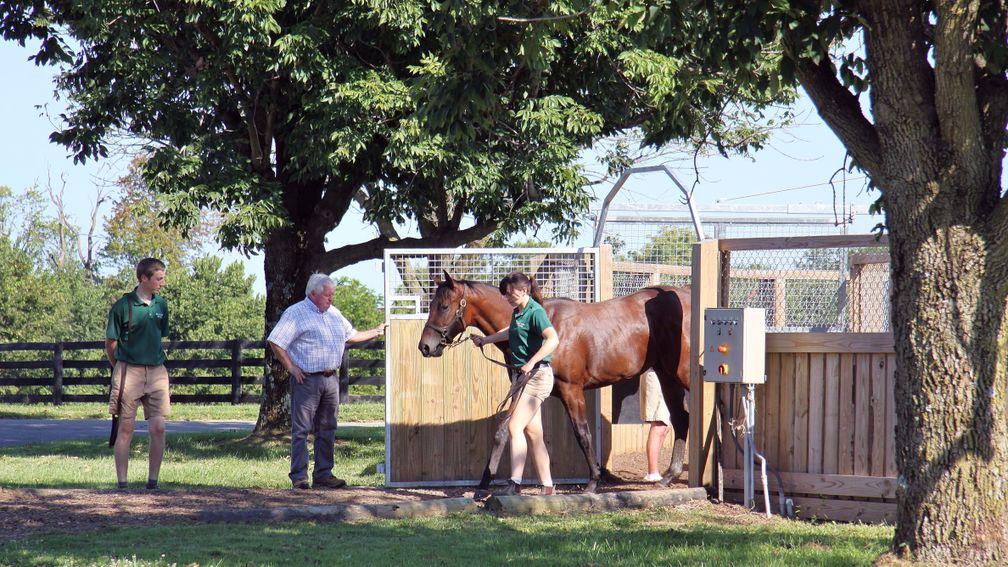

"You can do all the courses and still you're not a horseman," Dilger says. "When I started out, there were no [mobile] phones, no running to offices and here and there. The old stud grooms went in every morning, took care of the horses all day long, made sure every horse had eaten up every evening. They were just completely natural around the horses. They could see an animal getting sick before he got sick. That's the way their eye was trained. They depended on getting the horse right themselves.

Herdsman

"There are very good young people today, who handle horses well, and they're more advanced in technology. Years ago we wouldn't know scientific names. But you cannot get other things out of a book - the herdsman, as I call him, being well able to feed and care for them, to know when horses are going forward; or when this guy should maybe get a little more attention than the next.

"They knew how to feed. Throwing it into a bucket, that's not feeding. Today the feed companies have it all mixed. The old timers, they'd be boiling that bran all day, the oats would be cooking. So it's different times."

As such, the one imprint he will acknowledge on his Derby winners is a collective, cultural one. For the regime at Dromoland, he protests, is no different from similar outfits operated by other exiles in the district: hands-on, day by day, never more than a couple of minutes from kitchen to paddock.

It must be said that Nyquist did rather more for Dilger’s reputation than his pocket. From the first crop of Uncle Mo, he was bought as a foal at Keeneland for $180,000 with Ted Campion and Pat Costello. Dilger remembers coming into the back ring, a mutually appraising encounter with Campion. "Are you on this horse, Gerry?" "Yes; you?" "Yeah. Will we split him?"

Rangy

"We'd all had our homework done, had him vetted, knew he was clean, a good throat," Dilger says. "He was good-sized, rangy foal, with medium to good bone. But from the side he was very nice, very good angles and you could see where he would grow into. Wasn't 100 per cent perfect in front, but he was fine. Even as a yearling he wasn't a big robust horse. Some of these Uncle Mos, they might have beautiful stretch, size, you know, but they’re not big heavy horses."

The following September, the colt was sold through the same ring to Mike Ryan for $230,000. Ryan was a good friend; in fact, he and Dilger shared a handful of mares in a minor-league breeding partnership they called Santa Rosa. "He's a nice horse, Mike," Dilger had told him. "He's not done a thing wrong, we've never had a bandage on him. So what you see there, Mike, that is what you're getting."

It was a pretty marginal pinhook, when split three ways. But all involved - Dilger and his partners in the horse, and Ryan himself - at least reiterated the shared, shrewd knack of the men who put the green into the Bluegrass.

The reserve had been set at $224,000. That's how close they came to keeping him, pushing on towards the breeze-ups themselves. But you never know how these things will play out. Fatefully, for instance, one more bid might have made all the difference when Dilger and Ryan had offered one of their Santa Rosa mares, Above Perfection, at Fasig-Tipton November in 2009. They were trying to cash in after the foal she was carrying, when purchased for $450,000 at the same sale three years previously, went on to win the Grade 1 Spinaway as Hot Dixie Chick. In the event, they were left wondering whether they had been too greedy after buying Above Perfection back for $1.15 million.

"I'd say if there had been another bid she'd have been gone," Dilger admits. "Yes she was on the brink of her reserve. And we'd have been absolutely delighted, you know. Instead we took her home and it was: 'Well, like, we'll have to go on now with her.' So we did. At that stage it was too late."

Complementary

In 2013 it was decided to try Above Perfection with the freshman Bodemeister. Though the mare had been very fast - beaten only a neck by champion Xtra Heat for the Grade 1 Prioress over six furlongs, the pair gunning from the gate - not all her foals had been compact, sprinting specimens like Hot Dixie Chick. Dilger liked the complementary build in Bodemeister; and of course remembered how he had carried his own terrific dash to a heart-breaking margin when collared late in both the Kentucky Derby and Preakness.

The resulting foal, as a homebred, had longer exposure to the Dromoland system than its standard weanling pinhooks. By increments, by recycled profit, it had long become clear that this could only be to his advantage. One of Dilger's breakthrough sales had been Tomahawk, a $2.5 million Seattle Slew yearling who became one of Aidan O'Brien's earliest crack juveniles. From the same crop, moreover, Dilger also consigned Elusive City who won the Prix Morny for his mentor's son Gerard Butler; Tomahawk and Elusive City, in fact, filled the podium behind Oasis Dream in the Middle Park.

One way or another, Dilger has plainly mastered the nuances of bringing youngsters on, not least through the rigours of the Kentucky winter. "I think it's very good for them, they do way better in the cold weather," he insists. "Because they've good healthy coats, they're out and around, they're running together, they're playing. Icy rain is a different ball game but snow doesn't bother them. Feed them well in the mornings, throw them lots of hay, make sure they can drink plenty of water, break their troughs. But they're healthy, they're happy. And you see them developing.

Natural

"People have their own ways, and there's not a thing wrong with that. Weighing them every month or whatever. But as I said to the feed man: 'I'm going to buy your feed - but if I need you to weigh them, to tell me if they're putting on weight or growing… Well, I shouldn't be here.' Simple as that. Keep it the old way. Just keep it as natural as you can. Those horses will do it on their own.

But it is not just with his own herd that Dilger has a finger on the pulse. His Bodemeister colt, sold to Steve Young for $350,000, made an overnight sensation of his sire as Always Dreaming; and Dilger had already caught both Tapit and Pioneerof The Nile on the way up with the same mare. Unsurprisingly Above Perfection's latest assignation was with Nyquist. "He's been good to me so we'll be good to him!" Dilger says. "She's 19 now but she looks super, she looks 14."

Again, however, he is adamant that the Midas touch only reflects the company - and competition - he keeps. "It's got very selective," he observes of the pinhooking of weanlings. "More people are doing it, and when a real nice foal with a nice pedigree comes into the ring you won't be lonely standing up there. You might be waiting all day long, see nobody, I don't know where they'd be hiding - but by Jesus they come out of that woodwork. And they're probably saying the same about me."

None of them has rules, or manuals; just intuition. As such, Dilger views his remarkable Derby double as a shared one; a credit to his whole circle of friends and rivals, and the way they do things.

Puzzle

"This whole thing is a puzzle," he shrugs. "People now are doing horses' hearts. Well, that’s another piece of the puzzle. They're doing their stride. Another piece. Genetics stuff. Piece of the puzzle. But you can have all this - and if they're not sound, they can't run.

"And it will surprise you. Same way you'll see very good under-16 hurler, good at 18 still, but at the next level they don't get stronger, they don’t grow. And they're done. And that weakly lad that can't get into the under-16s, there he is now, hurling the life out of all of them. So it's a never-ending process. Certainly I can't get the whole picture from a foal.

"The luck just happened to run my way the last couple of years. It's great for the farm, and the team. But my feet are still on the ground, now. I know how hard this is. I know how much you have to get lucky." He pauses, gives a wry laugh. "But everyone else has to get lucky too."

Published on 6 February 2018inFeatures

Last updated 17:03, 6 February 2018

- Under the bonnet - the pedigrees behind the 1,000 Guineas field

- Classic clues: a look behind the pedigrees and background of the 2,000 Guineas field

- 'It was like winning the lottery, it's unbelievable' - Strong Leader shining for the Rainbows after Aintree triumph

- 'I hate running, unless it’s after a hockey ball, and love chocolate!' - Q&A with York charity race rider Pippa Harvey

- How a 'Saturday girl' paid in doughnuts realised a lifetime ambition of owning a racehorse

- Under the bonnet - the pedigrees behind the 1,000 Guineas field

- Classic clues: a look behind the pedigrees and background of the 2,000 Guineas field

- 'It was like winning the lottery, it's unbelievable' - Strong Leader shining for the Rainbows after Aintree triumph

- 'I hate running, unless it’s after a hockey ball, and love chocolate!' - Q&A with York charity race rider Pippa Harvey

- How a 'Saturday girl' paid in doughnuts realised a lifetime ambition of owning a racehorse