'I've never been so terrified' - bomb threats, booze and the Monday National

Senior writer Lee Mottershead recounts with key people events of 25 years ago

This article was first published on April 2, 2022, 25 years on from the dramatic 1997 Grand National, which had to be postponed two days and run on Monday rather than Saturday after a bomb threat forced the evacuation of Aintree racecourse.

This feature has been made free to read as an exclusive for uses of the Racing Post app – to get more of the best features, exclusive news and expert advice from our team of top tipsters, subscribe now to Racing Post Members' Club and enter the code SAVENOW to get 50% off you first three months.

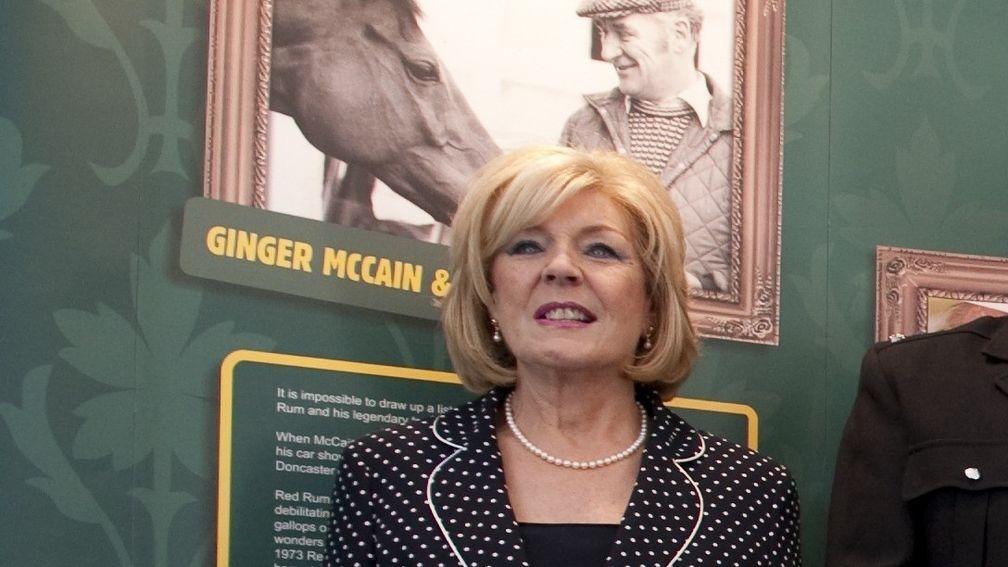

The 1997 Grand National was less than an hour away. Princess Anne had already unveiled a bust of Sir Peter O'Sullevan, the broadcasting legend about to call horseracing's signature event for the final time. The field for the Aintree Hurdle was beginning to assemble near the start. Then the phone rang.

At 2.49pm a call was made to the Aintree University Hospital. An individual in a phonebox, claiming to be from the IRA, stated there was a bomb somewhere on Aintree racecourse. The device, it was said, would be detonated at 4pm. Three minutes after the first call, a second was received in a police control room. The warning was the same. The 150th running of the Grand National had been targeted by terrorists.

Only four years earlier British racing had been left humiliated by the Grand National that never was. This was altogether more serious. The United Kingdom was well used to attacks by the IRA, which just two days earlier had issued threats that caused three motorways to be closed. Sometimes the threats were all too real. With 60,000 people inside Aintree, the potential consequences of an explosion were unthinkable.

Aintree managing director Charles Barnett was at the top of the Queen Mother Stand when he heard the news from a senior police officer. As Bimsey was winning the Aintree Hurdle under Mick Fitzgerald, Barnett was informed the threats had been verified. The phonebox caller had used a recognised IRA codeword. Aintree would have to be evacuated.

The Grand National field was in the paddock when the millions watching BBC1's Grandstand coverage were told something was wrong. As Richard Pitman and Peter Scudamore talked about the runners an alarm could be heard in the background. "They are evacuating the County Stand," Pitman said. "There has been some sort of alert and this will just delay proceedings for a little while."

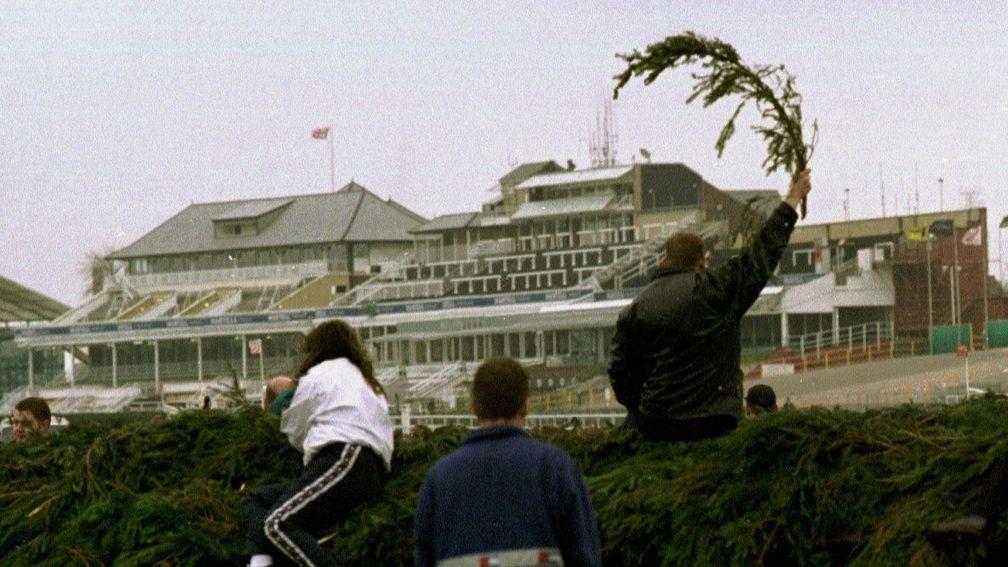

A few moments later, as television pictures showed running rails being lowered and spectators walking on the track, Pitman added: "We hear the whole course is being evacuated. What happens from here, I just do not know."

Nor did the Grand National jockeys. They were told to leave. Everybody was told to leave. The biggest evacuation since the Second World War had begun.

Jamie Osborne, rider of Suny Bay

We were asked to get out of the weighing room but we didn't know why. In our minds we thought we would just be hanging around outside for five minutes. We had no idea what was about to unfold, so we were all just in breeches, boots and colours. It was bloody cold as well.

Charles Barnett, Aintree managing director

We had to get the message across that this was an urgent situation and people couldn't just hang about. Did I think it likely there was a bomb? Not really. There are so many Irish people in Liverpool and there would also have been so many at Aintree. Even so, we couldn't be certain. The police didn't want to muck about.

Ian Renton, Aintree assistant clerk of the course

After clearing everyone from the weighing room I was about to go in there myself to collect a rules book I thought I would need. A member of the police team saw me and told me I had to leave. I told him I was just about to go. "No, you need to go now," he said. Then he added: "Run, don't walk. Now!"

Not everyone was running in the right direction. As people fled the grandstands, jockey Charlie Swan was running towards them, desperate to get for boss JP McManus the plastic bag that contained his betting money. It was a successful endeavour. Others weren't so fortunate.

Nigel Payne, Aintree press officer

Peter O'Sullevan was in the weighing room when the evacuation began. He wanted to go back into the County Stand to collect his briefcase and binoculars but was told that wouldn't be permitted. You can imagine how 'The Voice' reacted. He was adamant with Merseyside Police chief inspector Sue Woolfenden that if he couldn't get his belongings they would disappear. She assured him that wouldn't happen but he wasn't convinced.

He told her: "I'll bet you an even nifty they won't be there when we come back." Not surprisingly, Woolfenden didn't understand what he meant.

When he was told the following day that all his stuff was still in place, I took him over to Woolfenden and he gave her £50. "I can't take that," she said, to which he replied: "Well, in that case put it in your police benevolent fund."

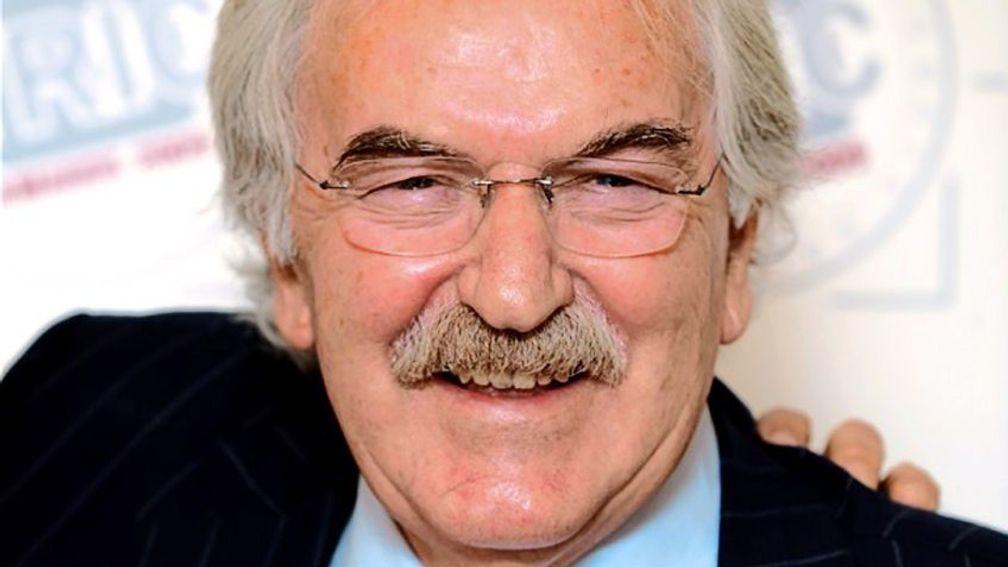

Anchoring the BBC's coverage was Des Lynam, a Grand National veteran of many years.

Des Lynam, Grandstand presenter

At the end of each Grand National I would say, "I'm never doing that again". I suppose for me the Grand National experience was a bit like childbirth – I always forgot how bad the experience was, so I went back and did it again.

On this occasion, he was told he had to stop doing it.

Two superintendents came across to my position and said, "Follow me", so I followed them. I ended up in a queue that was being led by Princess Anne and the film star Gregory Peck. Suddenly it dawned on me that they were taking us off the racecourse. "Eh, Des, what are you doing, leaving?" a few racegoers asked. "'Hang on a minute, hang on a minute," I said to the police. "I'm presenting this programme. I can't leave."

I wasn't ever frightened. I was annoyed. When the Merseyside Police look after you they really look after you. They are big fellas and they carry big sticks.

While Lynam was being escorted to a new position in the horsebox park, the BBC's Jim McGrath was in sole charge of talking viewers through the unfolding drama from his commentary position close to Becher's Brook and the Foinavon fence.

Jim McGrath, BBC Racing commentator

We were preparing to leave when our director Malcolm Kemp said: "Stand by, Jim." I had no idea what I was standing by for. Then I got the five-second countdown and I was on. It was completely out of the blue. I thought we were going to be told to evacuate like everybody else but they forgot about us, so we just kept going.

Somebody timed it and told me I did 13 minutes 50 seconds. At no point did I have any thoughts of drying up because I couldn't afford to. Malcolm had told all the cameramen to lock their cameras in position, so I just talked over the pictures and kept repeating what I knew to be true. It was only in the last minute that I thought: "Gee, this has been going a fair while."

Once Des was definitely in position – by when the security guards had found us – we hotfooted it down on to the track, walked past Valentine's and on to Anchor Bridge. Like a lot of other people, we ended up in the McDonald's not far from the main racecourse entrance. It was there that I caught up with my BBC commentary colleague John Hanmer. I don't think he had ever been in a McDonald's. I doubt he's been in one since.

McGrath and Hanmer were not the most famous diners in that fast-food establishment.

Julian Armfield, reporter for The Sporting Life

Having observed my press badge, Gregory Peck asked if I knew where he and his entourage could get some food nearby. I told him his only hope was the McDonald's in the Aintree Retail Park.

We marched down there and he kindly asked me to join him for a Big Mac and banana milkshake.

Over lunch, perched on giant toadstool seats, we talked about his films and his love for the Grand National. He explained that watching Different Class carry his colours into third place behind Red Alligator in the 1968 race was the thrill of a lifetime.

Peck would not be seeing a Grand National that day. Not long after Lynam had resumed broadcasting, he carried out an interview with Barnett. What followed was one of the most famous encounters in the history of Grand National broadcasts.

"Des, this is tragic," said the Aintree chief.

"Everybody will have to leave, including you the BBC. There have been two coded bomb warnings received by the police and there is no possibility of taking any chances. Consequently, we're going to abandon racing for today and make a further announcement later.

"So I'd just ask everybody here – including you from the BBC – to leave the course and get out on to the public highway immediately."

As Lynam said his goodbyes, a somewhat stunned-looking Gary Lineker, then in his infancy as a BBC presenter, found himself steering the Grandstand ship. In charge of a considerably more significant operation was Merseyside's assistant chief constable – and future BHA board member – Sir Paul Stephenson, who travelled from his home to police headquarters at Canning Place in Liverpool.

Sir Paul Stephenson, Merseyside Police assistant chief constable

I can't remember a more difficult crime scene. We had to seize 4,000 cars and evacuate more than 60,000 people. There was also a huge amount of property, including cash, left behind. We also knew the majority of those 60,000 people were not equipped to spend the night on the streets of Liverpool, so we had to find them beds and blankets.

While the evacuation was taking place, Barnett and Aintree chairman Lord Daresbury were driven by police at high speed towards Canning Place. Right behind them in a separate car were Judith Menier, PR director for Grand National sponsor Martell, and Payne. It was not an enjoyable trip.

Nigel Payne

I don't mind saying I've never been so terrified. The policeman in the front passenger seat was holding a huge semi-automatic and the driver never once seemed to look at the road. He relied constantly on his pal, who said things like "bus on the left" or "traffic lights coming up". A trip that would normally take about 20 minutes took only seven.

Once Stephenson and the Aintree team got together it became apparent they had different priorities. Stephenson wanted to ensure the racecourse site was cleared and made safe in order that a full investigation could be carried out. Barnett and Daresbury wanted to get the Grand National run as soon as possible.

Daresbury also wanted something else. The former top amateur jockey – a winner over the Grand National fences 15 years earlier – was afflicted at the time with gout. While at Canning Place he was in pain but without his painkillers. Those with him were also ravenously hungry. Daresbury succeeded in getting delivered to the city centre command centre not just medication for his feet but also sandwiches for his team.

Meanwhile, as racing luminaries enjoyed food and beverages in McDonald's or Liverpool's police headquarters, many of those who had expected to be involved in the race were benefiting from the hospitality of Edie Roche. As racegoers started to fill the streets of Aintree and then further afield, the people of Liverpool opened up their homes. No home was busier than 47 Melling Road.

Edie Roche, Aintree resident

My house was party central. All the jockeys were there in their silks – and once they knew the race definitely wouldn't be taking place that day it really did become a party. Luckily, we're a large family, so we were well stocked, especially with alcohol.

There must have been 100 people in the house. We honestly couldn't have fitted in another person. The creme de la creme was here. I had no idea who they all were, but we even had Willie Carson and Jenny Pitman.

The last two to go were a very famous trainer called Nicky Henderson and the lady who was then his wife. They were waiting for their driver to pick them up. By that point we had run out of gin and whisky, so they finished up on the lager. I remember the wife saying she quite liked the stuff. They only left at half seven because my husband, Vinnie, and I were going out for a meal. The following year I was standing at the door and I saw Mr Henderson wanted to come in again. His wife had to drag him away.

Out of unfortunate circumstances it became a day to remember – and, you know what, I've been living off this story for 25 years!

After leaving Roche's house, her jockey guests headed into the city. They were not planning for a quiet night.

Jamie Osborne

A bunch of us walked to a station and got on a train. As we didn't have any money we must have jumped over the barrier. They're probably still looking for us. There were ten to 20 blokes wearing racing silks in a packed carriage. We looked like a stag night. Then and afterwards I remember hearing lots of that unbelievably good Scouse wit, including from the doorman at the Adelphi hotel, who saw me and said: "Eh, mate, have you come straight from work?"

Tony Dobbin, rider of Lord Gyllene

The rest of the lads were heading out to party in Liverpool, so I was quite jealous, but I decided to head home. Barry Murtagh drove down and picked me up from the motorway roundabout. All I was wearing was the Lord Gyllene silks, boots and breeches. I didn't even have a coat. A young kid cycled past me and shouted: "Only girls wear boots like that!"

The horses who should by then have run in the Grand National were eventually permitted to leave the crime scene – where police carried out three controlled explosions – and taken to Haydock. Thousands of racegoers also needed shelter. They found it in the homes of strangers or a school's sports hall. One couple slept in the sauna of Feathers Hotel. Liverpool rode to the rescue of its visitors.

Back at the racecourse, Barnett's team had been allowed back to organise essential tasks. Once those had been arranged, their next destination was the chairman's family pile.

Nigel Payne

We left the racecourse at 8.30pm and were then going to Daresbury's house to make plans. Back in those days the Jockey Club had a head of security called Roger Buffham, who wanted to be involved in all the discussions. Charles didn't like the thought of that because he felt we should only be dealing with the police. I therefore told Buffham we would be meeting at The Grosvenor Hotel in Chester and that he should ask for Lord Daresbury's suite when he got there. I have to admit, it was a terrible thing to do!

A few regrettable things were also about to be done in the hotel preferred by the sport's top jump jockeys.

Jamie Osborne

I had always wanted an excuse to go to a nightclub in a pair of breeches and boots. That night underneath the Adelphi I finally did – and I wasn't the only one! Everyone just let themselves go. Nobody gave a toss about their weight or anything else. We were just a group of boys having a nice time. Unfortunately, we all got hammered, which wasn't an ideal preparation for riding in the Grand National, particularly as some of the lads became 10lb heavier through the Saturday night.

In the early hours of Sunday morning at Lord Daresbury's home – where there was no sign of Roger Buffham – Barnett and Renton were having trouble sleeping in their shared bedroom.

Ian Renton

At 4am, by when I couldn't have had more than two hours of sleep, I said to Charles: "Are you awake?" Like me, he couldn't stop thinking. We went down to the kitchen and continued the conversation over coffee. By about five in the morning we had gone through every conceivable option and concluded the only way to proceed was to run just the Grand National on the Monday.

Yet that could only be done if Merseyside Police agreed to put its reservations to one side. Fortunately, also a guest of Daresbury was Sir Nicholas Soames, a Conservative minister in John Major's government, who was asked to contact home secretary Michael Howard. By doing so, he may well have saved the 1997 Grand National.

Sir Nicholas Soames, Conservative minister

I did what I could to help. I spoke to the home secretary but it must be stressed that the entire racing industry showed real leadership. They showed drive and determination. To get that race run, the Aintree team and everyone involved achieved something remarkable.

After Soames lobbied Howard, the home secretary made a call to Stephenson. The latter remembers it clearly.

Sir Paul Stephenson

Aintree might have sought to use political influence to put pressure on us. It is certainly true to say Michael Howard made us – to phrase it as a barrister might – properly aware of the consequences of the Grand National not being run.

I think the conversation went something along the lines of: "Before you make a decision on whether to allow the race to be staged, you need to be aware of certain facts; one, if it does not take place, there is the potential danger the Grand National will never be run again because of its history and difficulties with sponsorship, an outcome that would represent a great victory for a terrorist organisation; two, there would be a significant loss to the exchequer from gambling revenue; three, the prime minister intends to come."

He made all that clear but then said the decision was entirely mine!

Cops will always insist we're operationally independent without fear or favour. However, politicians of all persuasions will bring upon us pressure, while trying to stay within the boundaries of propriety. That is entirely appropriate. It's then up to the cops to make their own decisions.

What politicians say does inform those decisions and it would be fair to say I wasn't unaware of the significant pressure falling on my shoulders.

Michael Howard, home secretary

I fear my recollection of the details of those events is very hazy. I should just add that I doubt John Major would have needed much persuasion. We were all keen to show that the IRA couldn't permanently disrupt one of our great sporting occasions.

It was announced on the Sunday morning that the Grand National would be held at 5pm the following day. Admission would be free and the BBC would televise the contest as usual.

Through Sunday, people were allowed to collect cars under police authorisation. Aintree's groundstaff began repairing fences that had been damaged during the evacuation and jockeys worried about the many pounds packed on the night before.

Soon enough, Grand National day dawned once again, with Renton on the track from 3.30am. It was only at 2pm that the police handed full control of the racecourse back to Aintree. Stephenson had not slept since Saturday.

Around 20,000 people came, including John Major, just weeks away from losing power in a general election. His presence, and that of Princess Anne, only made the occasion more attractive to terrorists. Perhaps not surprisingly, two more coded warnings were received shortly before the race was due to start. Stephenson concluded that if there was a bomb it would likely be in a most unusual place.

Sir Paul Stephenson

We believed our only potential weakness could be around the newly erected statue of Sir Peter O'Sullevan. I wanted to ensure I knew the identity of every person who had wielded a shovel when the foundations were dug. I also wanted to ensure whoever was making the phone calls on behalf of the IRA did not think we were ignoring them.

The IRA would have had people watching at Aintree and also people watching the BBC coverage. The more bomb warnings you get, the more pressure falls upon you to abandon. I needed the IRA to think they might have succeeded in their plans, so we carried out a small evacuation around that area.

We were confident there was not a device at Aintree. Had I not been confident I would have abandoned the race. To have not evacuated the public following a coded warning from the IRA was probably unique.

Probably also unique was the alleged generosity shown to some of the 36 riders about to compete in the year's biggest race.

Jamie Osborne

Now time has passed I think it's okay to say a delegation of jockeys went to the clerk of the scales. It had become apparent the amount of overweight was going to be a huge embarrassment. As a result, a little bit of cheating took place.

In the modern era heads would roll, but on that particular occasion an agreement was reached with the clerk of the scales that we wouldn't sit on the scales for too long. There just might have been a couple of cases of extreme overweight that weren't recorded.

I know that almost amounts to deception but given the strange circumstances I hope people feel it was okay for a bit of leniency to be shown.

Osborne finished second on Suny Bay, 25 lengths behind the contest's 150th winner, Lord Gyllene, owned by Sir Stanley Clarke, trained by Steve Brookshaw, ridden by Tony Dobbin and called home by Sir Peter O'Sullevan, who bowed out by reflecting: "All this shows it's very difficult to deter the Scousers."

Tony Dobbin, rider of Lord Gyllene

A lot of my mates say it doesn't count because it was a Monday National. It counts to me. My God, it was out of this world. It was all my childhood dreams coming true.

I can remember pulling him up, leaning down and giving him a hug. For a couple of seconds it was just me and him. Then I lifted my head and suddenly we were surrounded by people.

It was what every jockey dreams of doing. I'm blessed that it happened to me.

Sir Paul Stephenson

When the race finished, I was extraordinarily relieved.

Before the race John Inverdale asked me if I would give him an interview for BBC Radio as if the race had been run without any problems. He was adamant if something did go wrong the interview would be destroyed. I would never normally have agreed but I trusted John, so I did the interview and it was played shortly after the race.

It was a phenomenal team effort from the cops, the racecourse and beyond. It would have sat very badly with my conscience had we ended up unable to withstand the threat of a ten-pence telephone call. For that reason, I was actually very grateful for the pressure placed upon us to run the race. To put it bluntly, it meant we were able to raise two fingers to terrorists.

Much less documented is the fact that in 1998 we had a far more serious threat in terms of what was being planned. What I can say is we managed to interdict something we were confident was coming our way on the Thursday. This time it was not a hoax.

My experience of the Grand National convinced me horseracing and I should never again be put together. That does, with hindsight, seem bizarre given I became the regulator for the British Horseracing Authority. By then, however, I had recovered from the trauma and forgiven horseracing.

Charles Barnett

The Grand National is more than a horserace. It's a national event. We felt really strongly that somehow or other we had to make it happen. Fortunately, we were helped by some outstanding police officers.

After 1997, and because of the enormous publicity it generated, I think the people of Liverpool remembered the Grand National is their race and Liverpool's race. It boosted the race's attraction locally, nationally and internationally. It was another great Grand National story.

Read these next:.

'Robust policing plans' in place for Grand National day after reported sabotage plot by activists

Sixteen horses scratched from the 2023 Randox Grand National as 57 stand their ground for Aintree

Get 50% off Members' Club Ultimate Monthly for three months! Unlock the Racing Post digital newspaper and full site access for less, with 50% off your first three months of a subscription to Racing Post Members' Club. Be the punter in the know for major upcoming festivals including the Grand National, Qipco Guineas festival, Royal Ascot and more. Subscribe today*.

*Available to new subscribers purchasing Members' Club Ultimate Monthly using code SAVENOW.

First three payments will be charged at £19.98, subscription renews at full monthly price thereafter.

Offer expires April 15, 2023, 11.59pm.

Published on 2 April 2023inApp exclusive

Last updated 11:36, 2 April 2023

- Sir Henry Cecil remembered: 'The public have always been fantastic to me and I really don't know why'

- Johnny Dineen's wager of the weekend

- 'To win that far he has to be something else' - Kieren Fallon and Jason Weaver's best bets on our expert panel

- 'At 10-1, I'm in' - Paul Kealy's five horses to take from Epsom's Derby meeting

- I thought I could win the National - but in five strides it all went up in smoke

- Sir Henry Cecil remembered: 'The public have always been fantastic to me and I really don't know why'

- Johnny Dineen's wager of the weekend

- 'To win that far he has to be something else' - Kieren Fallon and Jason Weaver's best bets on our expert panel

- 'At 10-1, I'm in' - Paul Kealy's five horses to take from Epsom's Derby meeting

- I thought I could win the National - but in five strides it all went up in smoke