Demands of modern life run against requirements by breeders

Tom Peacock assesses the recruiting issues faced by the bloodstock industry

Racing is not, at least in the short term, one of the industries in the sightline as the machines continue their rise. While whip-wielding robot jockeys have managed to master camels, the nurture of a horse is largely a hands-on human job.

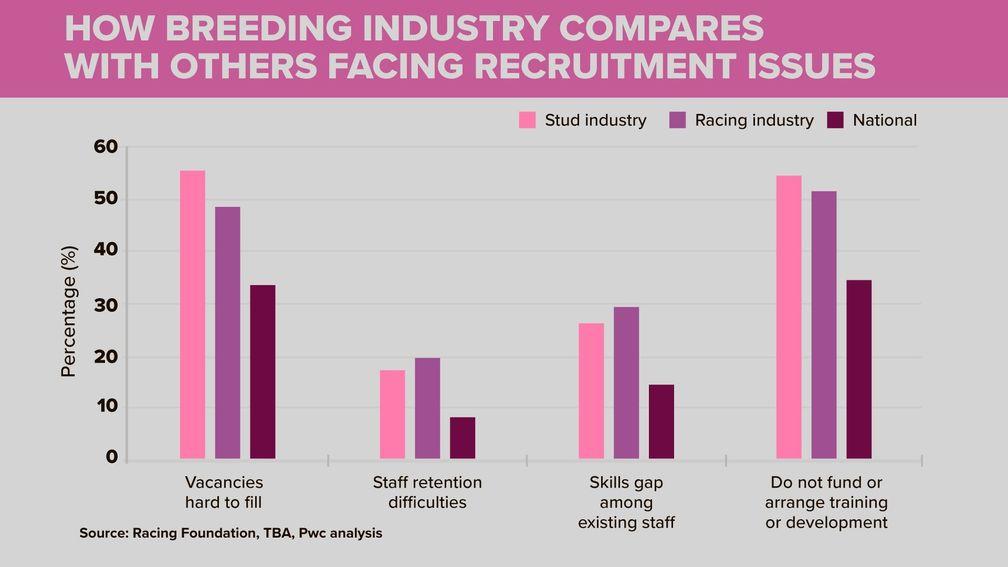

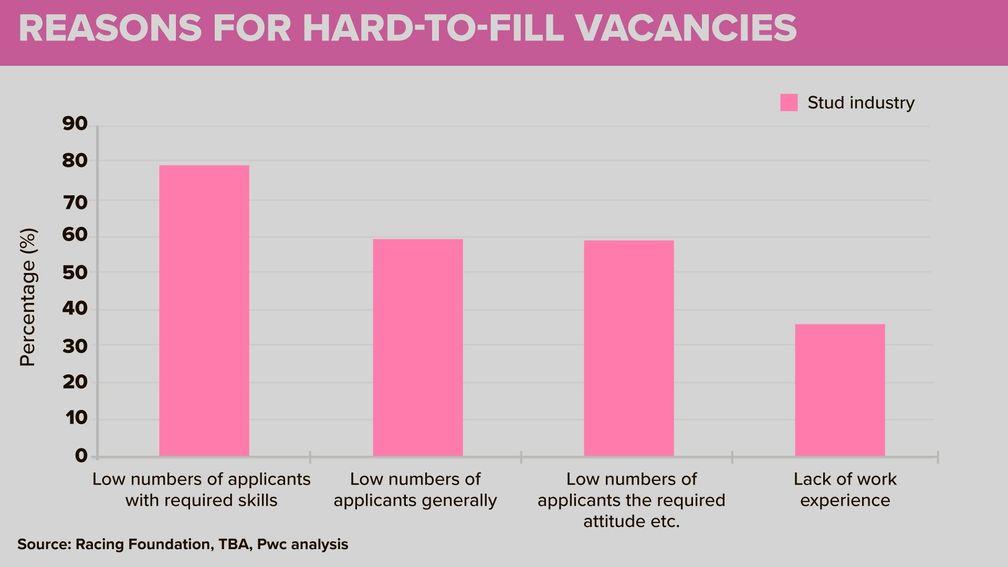

Yet apocalyptic warnings have been made of the staff shortage within racing stables and while the general consensus from those involved in recruitment is that the situation in studs has not become quite as serious, it remains a major concern with the most recent data showing 55 per cent of permanent vacancies in studs are hard to fill, compared to only 33 per cent of businesses nationally.

Last year’s Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association economic impact study also pointed particularly to a skills gap in the market of 26 per cent, compared with 14 per cent in businesses nationally. Around 3,500 people are directly employed in the breeding industry with an estimated annual vacancy of 15 per cent for permanent jobs.

The same issues, being repeated by operators across the country, are unsurprisingly similar to those experienced by trainers.

Simon Sweeting, manager of Overbury Stud, is grateful to have close to a full complement of predominately locally-based Gloucestershire workers, but admitted that he would not "necessarily be confident" of sourcing others at short notice.

"It makes me very nervous, the way things are going and how it does get harder and harder to find good people," he says.

"I hope we don’t try to take the mickey out of them, we try to make life easy and the job as fun as possible but ultimately the animals cannot look after themselves. If they’re standing in a stable they can’t fill their water bucket or get hay and feed, there has to be someone there seven days a week.

"A lot of the younger people who are coming in don’t seem to have quite the work ethic or the understanding that if you’re looking after animals there is going to be weekend work, and there might be after-hours work as well.

"There are obviously people who will do that, but there just seem to be fewer and fewer of them, and more who would happily work five days a week from 7.30 until four, but that’s all they want to do."

Stuart Thom has been involved at every level of the business, having been born on a dairy farm with a sideline in thoroughbreds and working his way up through the top studs on each side of the Irish Sea. He earned the 2016 Godolphin Stud Staff award for his work with Lofts Hall and has now started Galloway Stud near Royston. He has three full-time workers but is restricted by his premises.

"It’s hard to compete with the bigger studs," he explains. "Especially if, like me, you can’t provide accommodation, so it’s finding people in your area who will commute. It’s getting increasingly difficult to find experienced staff, and temporary staff even more.

"I think fewer people are coming into the industry because of the hours and the salary’s not as glamorous as in other jobs they could get. A combination of those things can put young people off."

Thom has established a link to provide opportunities for equestrian students from a nearby college but feels that they are a rarity.

"When I first started in Newmarket, every stud would have had a batch of half a dozen students every season and that doesn’t seem to happen any more," he notes.

"The rules and regulations of health and safety probably don’t help, it’s a lot more stringent now. When we take them from Milton College to give them work experience, you’ve got to have every box ticked."

An advantage studs have over yards is that most of their horses do not need to be ridden, theoretically opening them up to those without such skills or physique. This, however, is vital further down the line with Tracy Vigors explaining a year ago that her Hillwood Stud would withdraw from consigning at the breeze-ups due to a lack of available pilots.

Mark Dwyer, the former jockey who runs a sales and pre-training business at Oaks Farm Stables in Malton, says: "Riders are very hard to find, we’re dealing with a lot of yearlings and young stock and to find a guy who can do it from start to finish, they’re scarce.

"A lot of guys we want are ones who could be good enough to hold a licence - if that guy’s around here he’ll probably want to go and work in a racing stable with the chance of getting a few rides. We’ve got to compete with that."

He continues: "We’re all finding it tough, it’s an industry problem, not only in our business, everyone seems to be struggling for good staff. We’re on the edge of it, as we speak, but we’re getting it done. Going forward, [I’d worry] hugely."

Allied with the financial and social constraints, there are transparently wider issues at play, from racing’s fading prominence in the public's psyche to the altering of the rural milieu.

Brian O’Rourke, the managing director of the National Stud for more than eight years and now heading up Copgrove Hall, feels the issue is more cut and dried.

"You either want to do it, or you don’t. If you want to do it, you’re going to be motivated," he says bluntly.

"Not as many people want to do the physical side of it any more, but that’s just life. We have huge volumes of horses compared to what we had 25 years ago, and the same number of people coming into the industry.

"The thing is there’s too much racing, it’s seven days a week. If there wasn’t as much racing and more prize-money, it would help a lot of things."

It is only robots, after all, who never need a day off.

Brexit could bite

Implications for the racing community from Britain’s tempestuous departure from the European Community are as wide-ranging as for virtually any other industry.

Some 45 per cent of British studs employ at least one migrant from the European Economic Area on a permanent basis and the issue of possible restrictions for temporary workers is one which could particularly affect breeders.

The government has proposed a capped 12-month permit for all workers, as well as a minimum salary requirement of £30,000 for those with skills looking for longer visas, although they are proving as contentious as myriad other suggestions.

Simon Sweeting is unimpressed: "I’ve got one Polish guy who came over ten years ago, he’s still with us now and I hope he stays until he retires. One other guy is coming over from Poland, he’s happy to get on an aeroplane over for a month, and if he’s keen we’re happy to give him a chance.

"We used to have a lot of eastern European workers and I think it’s a very foolish thing for the government to say we can’t let them in at all post-Brexit because it’s just going to make life a lot harder for us. This £30,000 rule is moronic."

Ireland of course is unaffected by such worries but Maurice Burns, of Rathasker Stud in Kildare, paints an interesting picture of a cosmopolitan workforce.

"We have a few Eastern European guys who have been coming in for the breeding season for the last ten years," he says.

"Some of the guys are from areas in Poland, Romania, where there’s a good bit of agriculture going on and they know how to deal with animals. One guy just helps with the foaling, and he has a small farm in Romania, and he works that for the rest of the year. What he’d earn in the five or six months he’d work for me would be the equivalent of about three or four years’ wages in his own country.

"He has brought a few friends from his locality, who do the six months too. In a lot of these countries the horse is still a very important part of life. A horse is a horse, whether a thoroughbred or not. We find they’re very good workers and without them we’d probably be in trouble."

Published on inNews

Last updated

- Something different for Burrows as Group 1-winning trainer consigns at the Tattersalls Cheltenham December Sale

- Breeding right to Blue Point sells for €430,000 on Darley winning bid platform

- Classic hero Metropolitan set for strong home support with Etreham busy at the sales

- 'It has been nothing short of incredible' - Grace Hamilton on Godolphin Flying Start experience

- ‘She’s one of the best two-year-olds in Europe’ - bluebloods set to go down a storm at Arqana Breeding Stock Sale

- Something different for Burrows as Group 1-winning trainer consigns at the Tattersalls Cheltenham December Sale

- Breeding right to Blue Point sells for €430,000 on Darley winning bid platform

- Classic hero Metropolitan set for strong home support with Etreham busy at the sales

- 'It has been nothing short of incredible' - Grace Hamilton on Godolphin Flying Start experience

- ‘She’s one of the best two-year-olds in Europe’ - bluebloods set to go down a storm at Arqana Breeding Stock Sale