Why the lion's share of possession is no guarantee of victory

Wise words from the Soccer Boffin

Manchester City had 78 per cent of the possession at Brighton. Last season they averaged 65 per cent, the highest by a Premier League team since I started to keep records, which was in 2002-03. It was probably the highest ever. Tonight City play at home to Everton. How much possession will they have and what might it mean?

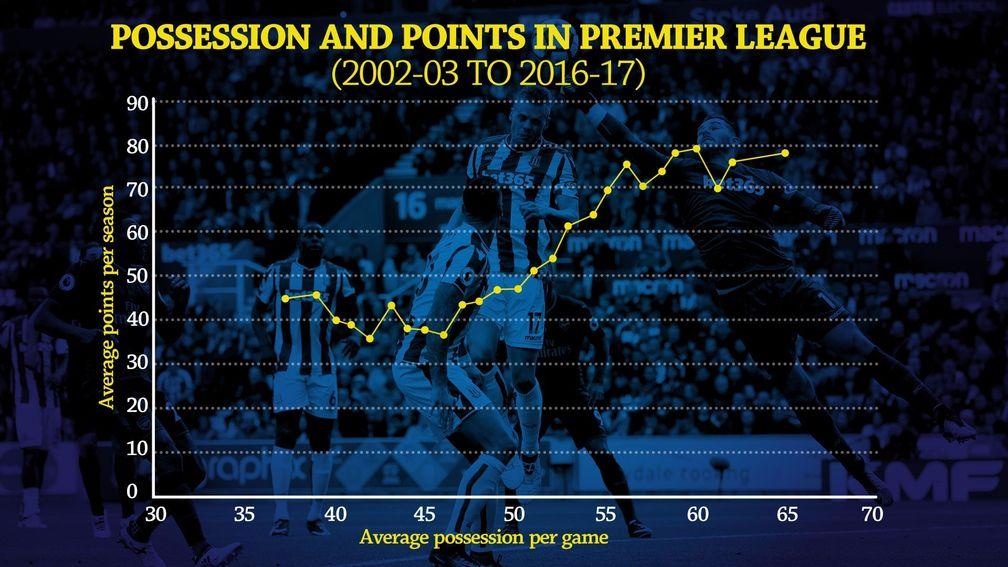

Possession is a strange thing. More is better than less up to a point. Teams with lots of possession tend to win more points than teams with only a little possession. Beyond a certain point, however, changes in possession-share do not seem to bring with them meaningful changes in results. In the Premier League at least.

You can see this on the graph. Teams with high possession generally did better than teams with low possession. But the graph does not rise in a straight line. It starts flat then rises then flattens again.

Teams with 47 per cent possession averaged in the middle 40s for points, and teams with 37 per cent possession averaged in the middle 40s for points. Teams with 56 per cent possession averaged 76 points and so, overall, did teams with even more possession.

If a team consistently have a different possession-share than other teams near them in the table it is probably because they prefer to play that way. It is a stylistic choice. For them it cannot be a sign of greater effectiveness because they are not getting better results.

Swansea averaged 57 per cent possession in the seasons 2011-12 to 2013-14, in which they finished between ninth and 12th. Having more possession means your moves last longer. Swansea’s moves lasted longer than those of other teams near the middle of the table. But at the end of those longer moves Swansea did not score more goals.

Tony Pulis-trained teams have low possession. West Bromwich average 38 per cent, Crystal Palace averaged 35 per cent and Stoke 40 per cent. They spend longer than their closest rivals without the ball, but they are good at defending and do not concede more goals.

Pulis knows that a Premier League team with an average defence is unlikely to be relegated – though Middlesbrough showed last season that they can be. Pulis’s teams have always conceded an average number of goals, which has been enough to keep them in the Premier League even though they have always scored a below-average number.

Pep Guardiola likes his teams to get the ball back quickly then keep it until they can make room for a shot. It is his style, which I along with many others enjoy watching.

Guardiola coached Bayern Munich for three seasons. They had 71 of the possession and scored 81 per cent of the goals in their Bundesliga matches. In the previous two seasons they had only 64 per cent possession but still scored 81 per cent of the goals. There was a development in style more than a change in results.

Even if Manchester City win the Premier League this season with 65 per cent possession they may not get better results than previous champions whose average possession was about ten per cent lower.

When wing backs need to press forward

Last season Manchester City attacked with a formation that was either 3-2-5 or 2-3-5. At Brighton in the first game of this season they attacked mostly in a 3-1-6.

At times when the score was still 0-0, which it was for 70 minutes, two of the three backs moved forward and there were nine City players in the third of the pitch nearest the Brighton goal.

Probably Pep Guardiola did not expect City to have that much of the ball. Otherwise he might have considered an alternative. When a team have so much possession so deep in the other half there is a case for saying that the highest, widest players should be wingers rather than wing-backs.

England, with less possession, did that at Euro 96. They got to within a penalty shootout of the final with a 3-4-3 formation that coach Terry Venables had copied from Louis van Gaal’s Ajax. The middle four were a diamond. Steve McManaman and Darren Anderton played as wingers not wing-backs. Leroy Sane and Raheem Sterling could do that on occasions for City.

Clock is ticking on debate over playing time

Football’s rule-makers – the International Football Association Board, or Ifab – published a discussion document in June called Play Fair.

A particularly interesting suggestion was to increase playing time by stopping the clock each time the ball goes dead. A match would then last for, say, 60 minutes of playing time rather than 90-plus minutes during many of which the ball is out of play.

At the moment average playing time in a match seems to be about 55 minutes. Last season in the Premier League average playing time was as low as 52 minutes and 33 seconds in Crystal Palace’s games but nowhere any higher than the 58 minutes and 10 seconds for Arsenal’s games.

Change may take a while, though, if it comes at all. Ifab’s proposals fall into three categories – those that could be implemented now because they do not require any alteration to the laws, those that are ready for testing and those that are ready only for discussion. Sixty minutes of playing time is only for discussion.

Published on 28 August 2017inBruce Millington

Last updated 15:28, 28 August 2017

- Vaccine offers hope that sport will open its doors and is something to celebrate

- DeChambeau's approach doesn't appeal to me, but his price certainly does

- We'd do well to pay greater respect to life's uncertainties

- Bruce Millington: celebrate the range of racing options rather than cutting back

- Villa are clearly on the up but theirs odds oversell the chance of a title miracle

- Vaccine offers hope that sport will open its doors and is something to celebrate

- DeChambeau's approach doesn't appeal to me, but his price certainly does

- We'd do well to pay greater respect to life's uncertainties

- Bruce Millington: celebrate the range of racing options rather than cutting back

- Villa are clearly on the up but theirs odds oversell the chance of a title miracle