A curious fox can give you more profitable tips than a prickly hedgehog

Wise words from soccer boffin Kevin Pullein

The Racing & Football Outlook Football Annual for season 1994-95 contained this good betting advice: listen to as many opinions as you can then make up your own mind. Even good advice can be hard to follow, though.

What are we to make of polar opposite opinions? You could treat them as answers in a poll. Six people say Manchester United will win, four say they will not. Perhaps there is a 60 per cent chance Manchester United will win.

Under certain circumstances this method will give you an accurate prediction. Under certain circumstances a crowd can be wise, as James Surowiecki explained in a book called The Wisdom of Crowds.

Unfortunately those circumstances are rarely found in heated betting debates. A crowd is wise, Surowiecki said, if it is large, diverse and each member gives their opinion independently without being influenced by others. You see what I mean.

You will have to weigh opinions one by one.

Psychologists have noticed what they call a confidence heuristic. The argument that is expressed with most conviction is the one that you are most likely to believe is right. Which is unfortunate because it is the one that is most likely to be wrong.

There is an inverse relationship between a person’s confidence in their argument and its accuracy.

As Philip Tetlock discovered.

Tetlock studied political and economic predictions. He contacted 284 experts: political scientists, economists and journalists. Over more than 15 years starting in the late 1980s he asked them 27,450 questions.

Their answers were awful. The experts would have been beaten, Tetlock said, by a dart-throwing chimpanzee.

Not all experts were awful, however. Most were really bad but some were quite good. The difference between them, Tetlock said, was in how they thought. The more confident an expert was that their prediction was right the more likely it was to be wrong.

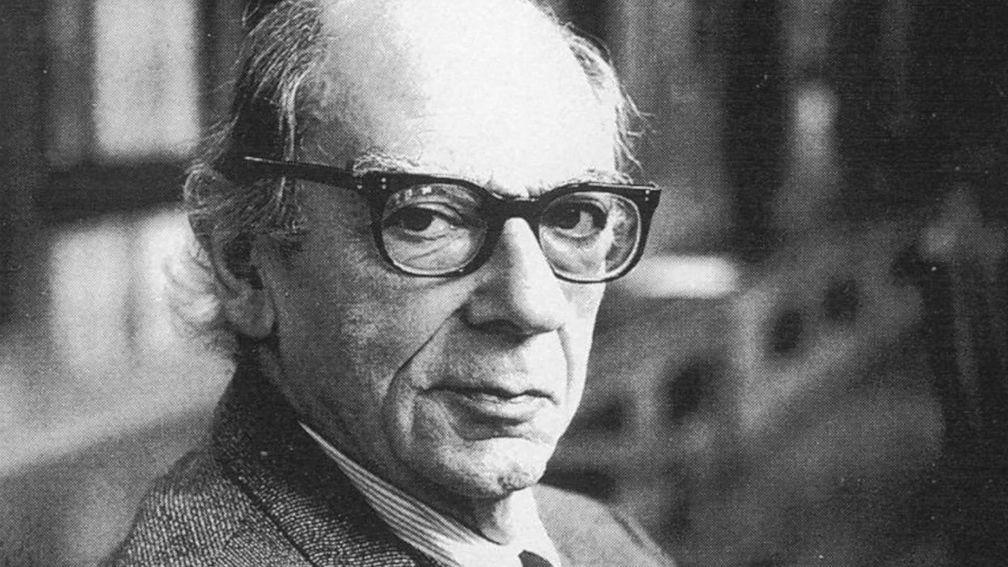

Isaiah Berlin, a 20th century philosopher, wrote an essay called The Hedgehog and the Fox. The title came from a line in an old Greek poem: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Berlin said that generally speaking there are two sorts of thinkers: those who are utterly convinced of a single idea and those who feel there might perhaps be something to be said for lots of little ideas.

Of the second group Berlin wrote: “Their thought is scattered or diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves, without… seeking to fit them into… one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes contradictory, at times fanatical, unitary inner vision.”

How Manchester City were crowned Premier League champions

The first group can be called monist, the second group pluralist. We might say that people in the first group are dogmatic and people in the second group are open-minded. Berlin called the first group hedgehogs and the second group foxes.

Tetlock borrowed those labels. He divided his predictors into hedgehogs and foxes. Hedgehogs were convinced they were right but were wrong more often than foxes, who had tried to balance lots of competing possibilities and were not at all sure they had found the equilibrium.

Hedgehogs made bad predictions, foxes made good predictions. There were more hedgehogs than foxes. Hedgehogs had one guiding principle. It did not matter what their guiding principle was, only that they had one. They saw the world in simple terms and made bad predictions because the world is not a simple place.

So when you hear conflicting arguments about betting, sport or anything else, try to do the opposite of what comes naturally – try to give more weight to any arguments that are couched in doubt. You will be doing the opposite of what most people do. That is often a good betting strategy anyway.

Scores fall as drama rises

When Lawrie McMenemy managed Southampton a journalist complained about low scores. If you want to see goals, McMenemy said, watch park football.

Most football watchers say they want to see high scores but their behaviour suggests otherwise. It did 40 years ago and it still does.

As we might be reminded next weekend in the FA Cup semi-finals when Southampton play Chelsea and Manchester United play Tottenham. The winners will go back to Wembley on May 19 for the final. What would you rather have – a ticket for the final or a ticket next season for a first-round tie of your choice?

More by Kevin Pullein

How everything and nothing has changed for West Brom

Weather predictions not to be sneezed at

Carlos Carvalhal is a wise old owl

Avoid pratfalls in the betting comedy of errors by copying serious actors

Follow the money to find the winner, just as they did in ancient Greece and Rome

Over the last 25 seasons – 1992-93 to 2016-17 – average goals per game were 3.0 in the first round and 2.1 in the final. Average goals per game were almost 50 per cent higher in the first round. Yet nearly everyone would prefer to watch the final.

What people do is a better guide to what they want than what they say. Next time you are walking in a park and see a football match count how many spectators are standing on the touchline.

The games people most want to watch are those between good teams when the result matters. In other words, games that are competitive and important. As competitiveness and importance rise, however, scores generally fall. The greater the number of people who watch a match, in the stadium or on television, the lower the number of goals they are likely to see.

Average goals per game in the FA Cup drop round by round. In semi-finals over the last 25 seasons average goals per game were 2.4.

Gianni Brera, editor of La Gazzetta dello Sport for a long time after the second world war, said the perfect game of football would finish 0-0. Every brilliant attacking thrust would be stopped by an equally brilliant defensive parry.

Like us on Facebook RacingPostSport

Published on 15 April 2018inBruce Millington

Last updated 19:22, 15 April 2018

- Vaccine offers hope that sport will open its doors and is something to celebrate

- DeChambeau's approach doesn't appeal to me, but his price certainly does

- We'd do well to pay greater respect to life's uncertainties

- Bruce Millington: celebrate the range of racing options rather than cutting back

- Villa are clearly on the up but theirs odds oversell the chance of a title miracle

- Vaccine offers hope that sport will open its doors and is something to celebrate

- DeChambeau's approach doesn't appeal to me, but his price certainly does

- We'd do well to pay greater respect to life's uncertainties

- Bruce Millington: celebrate the range of racing options rather than cutting back

- Villa are clearly on the up but theirs odds oversell the chance of a title miracle