Sad but inevitable conclusion to an association spanning over 100 years

Howard Wright on the departure of Tattersalls sales from Doncaster 60 years ago

Severance, a grey colt by Grey Sovereign out of the Blue Peter mare Top Standard: a name that means little nowadays, perhaps remembered only by the handful of eighty-somethings alive who backed him to win a two-year-old seller at Folkestone at odds of 100-6. Yet he does occupy a small place in racing history. Submitted by the Gibson family’s Highfield stud in Oakham, he was the last yearling sold by Tattersalls at Doncaster on Friday, September 13, 1957.

Friday the 13th – it was definitely unlucky for Doncaster, and Major John Priestman, the County Durham estates owner and upholder of the family’s coal-mining interests, clearly appreciated the sense of occasion when he named the soon-to-be-gelded youngster, who went into training with Geoffrey Barling in Newmarket.

Tattersalls had been in Doncaster since 1828 and selling yearlings there from 1840, taking over auctions organised by its northern counterpart John Boulton until his death that year. Then, the ‘sales ring’ was an open area in front of the Salutation Inn, close to the town centre on the busy trade and travel route of the Great North Road that ran the length of England from Newcastle to London.

A move to the Horse Fair ground in 1859 was followed in 1867 by the completion of a purpose-built, town centre facility at Glasgow Paddocks, named after the earl who used to board his mares nearby, although it could easily have been named for the great turf reformer Lord George Bentinck, who established a stud on the site to which he famously transported the gambled-on 1836 St Leger winner Elis in the first horse-drawn van.

There, Tattersalls developed the world’s premier yearling sales to coincide with September’s St Leger meeting. Although the fortunes of the fixture itself fluctuated – even in 1839 a correspondent in the New Sporting Magazine forecast that “the St Leger is a dying race, its days are numbered” – Tattersalls’ yearling sales continued on an upward trajectory after Doncaster Corporation bought the land in the early 1900s and built new boxes to lift the capacity beyond 350.

Even the intervention of the second world war, when the area was commandeered for use by the Royal Army Veterinary Corps, including the secretive production of vaccines for sick soldiers, could not interrupt success. When the site came back into commission in 1947, Tattersalls achieved an average of 1,827gns for 337 yearlings sold at Doncaster in September, compared with an average of 782gns at the two July sales and 817gns in October for similar ages sold at Newmarket.

The company’s tenure on Glasgow Paddocks seemed to have been secured in 1951 when, as recorded by Peter Willett in The Story of Tattersalls, partners Ken Watt and John Coventry were given sole rights to use the site, and they agreed an annual rent increase to £1,000 (£31,500 in today’s money), against £400 in 1920 and £550 in 1936.

The first hint of uncertainty came in 1955. On August 18 the Doncaster Gazette reported that two months previously the Race Committee, led by its formidable chairman, alderman Albert Cammidge, “met three times in eight days to consider a letter from Tattersalls about the future policy of the sales. The lease at Glasgow Paddocks ends in about three years and the Corporation planned an ambitious scheme at Red House Farm. The present site is scheduled for building development”.

The report added: “Tattersalls had considered this suggestion, said an official, and also a suggestion that the sales should be transferred to Newmarket, where they were held during the war years. ‘There is a large body of opinion for both sides,’ he said.”

Three weeks later, after the Queen had paid her third visit to the St Leger in four years but her first to the sales, a Gazette reporter wrote: “The rent for the new paddocks had been tentatively fixed at £6,000 a year, on a 99-year lease. Because of the high capital cost of the new paddocks, which initially will cost about £100,000, I believe the new rent will provide little profit to the Corporation. The full scheme will cost about £250,000.”

Meanwhile, at the eve-of-racing St Leger dinner, alderman Cammidge had been critical of Tattersalls, seeming to imply that the sales company had already decided to move its whole operation to Newmarket, while warning: “If Tattersalls desire to remain in Doncaster, the question of money must very seriously be looked at. We must look at it from a business point of view.”

To that and Cammidge’s other comments, Tattersalls made a lengthy, and tetchy, public response, pointing out what it believed to be a serious lack of communication and provision of detail from the Race Committee and castigating its chairman for “an unjustified attack at a public meeting”.

The statement, affirming Tattersalls’ “open mind as to the continuation of our sales at Doncaster”, concluded: “Let us hope that although this matter has started on these unfortunate lines, some satisfactory solution will eventually be forthcoming.”

In the event, neither side’s hopes were fulfilled.

The Race Committee’s proposed new site by the straight mile start at Red House, where Eddie Magner trained with decidedly limited success, never materialised. There was a five-year hiatus before Willie Stephenson and Ken Oliver resurrected bloodstock sales at the racecourse stables, and an age elapsed before part of Glasgow Paddocks became home to a new further-education college, which has since been demolished.

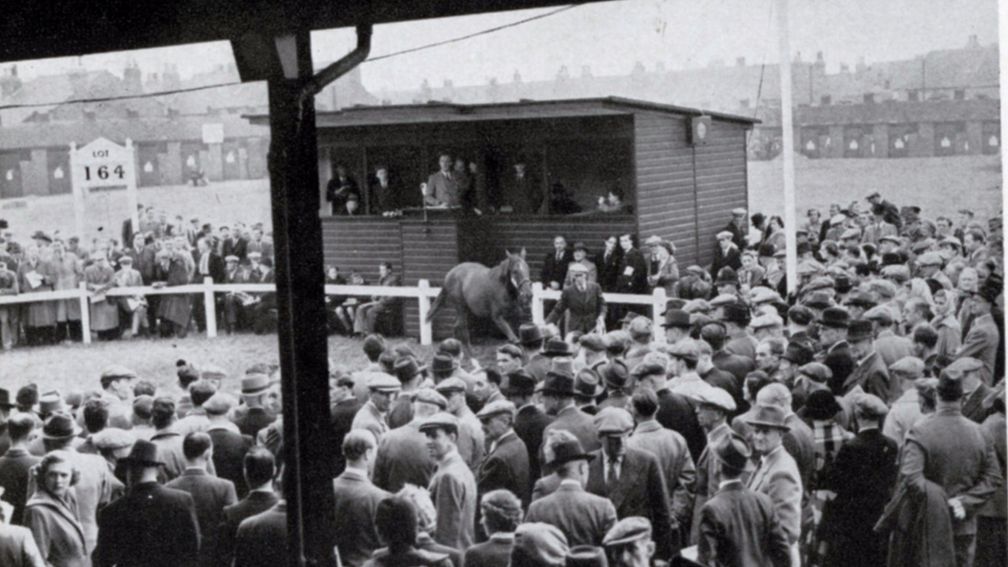

Through 1956, Tattersalls came to the decision it was time to move out of Doncaster. Willett’s history includes a graphic account of conditions at Glasgow Paddocks: “It was increasingly apparent that the facilities were woefully inadequate for the premier sales of their kind.”

He added: “The sale ring was pitiful in comparison even with the modest standards ruling in the Park Paddocks at the time. The ring consisted of a single white circular post-and-rail fence . . . located in a paddock of tufted, unkempt grass and the horses wore a bare earth track round the inside. The rostrum was in a ramshackle wooden shed. The stand was primitive, as if it might have been obtained from one of the minor National Hunt meetings.”

However, Willett attributed the reasons for Tattersalls’ exit to “the expiry of the lease, the Corporation’s requirement of the Glasgow Paddocks for civic development and the prohibitive cost of building suitable facilities at another site in the town.”

Ken Watt summed up from the rostrum when he opened the final yearling sales sessions: “It is with feelings of nostalgia that we leave here and that an era closes in Doncaster’s history. Doncaster Corporation and we at Tattersalls have examined this possibility [of continuing on another site] but it would prove uneconomic to both of us.”

Opinion among non-local racing folk appeared to border on resignation. The Bloodstock Breeders Review for 1957 paid scant attention to history, noting: “This was the last Doncaster sales. It is expected that the catalogue of the Newmarket September sales will be as attractive for prospective purchasers.”

The Doncaster Gazette quoted the Duke of Norfolk: “It is a great pity that the tradition of the Doncaster sales should die . . . I am sure the arrangements at Newmarket are perfectly adequate.” Esteemed trainer Captain Cecil Boyd-Rochfort reflected: “It is very sad, but it is inevitable.”

Local opinion was more prescient, at least as far as the impact that Tattersalls’ departure would have on the St Leger meeting and its significance to one week in the life and soul of Doncaster.

Speaking immediately before the 1957 meeting, the proprietor of Ye Olde Bell hotel at Barnby Moor, said: “Doncaster will find themselves catering for parties who bring their own lunch and buy bags of fish and chips. Anyone who thinks that the absence of the yearling sales from St Leger race week will not affect trade is a fool.

“My hotel is booked up to normal capacity. The American ambassador Mr Jock Whitney is due to arrive. Mr Jim Joel is bringing a party of ten, the owner of Ballymoss [the favourite and winner] has also booked in, as well as a number of other racing and sport personalities. Do you think these people will come for the sake of just a couple of days’ racing? I don’t.”

He was proved right, although Tattersalls’ decision alone cannot be held responsible for the fundamental changes that have occurred to the atmosphere of St Leger week over the last 60 years.

As chronicled by Tony Barber in his excellent history The St Leger, social and infrastructure developments have shaped the modern race meeting. Improved road networks, which preclude lengthy stays in houses whose tenants would use extra cash to go on holiday; closure or diminution of railway, coal mining and chemical works, with their one-week shutdowns; alterations to education schedules, which returned pupils to school before St Leger week, not after it; transformation of the local airport, which regularly decanted personalities such as Prince Aly Khan and Bing Crosby, into a lakeside settlement of houses and offices: they have all played a part.

Today, as the St Leger continues to fend off its critics, Glasgow Paddocks remains as a locality, but next week’s visitors who venture off the beaten track from town to racecourse will see no signs of its history, just a modern pedestrianised area of concrete and glass council offices, the police station and magistrates court, and a newly opened community theatre. Only the street names of Paddock View and Stable Terrace offer a clue to the past, locating blocks of new accommodation that stand incongruously close to the congested rows of Victorian terraced houses which have somehow survived.

As for Severance, he featured in the Tattersalls’ 1958 December sales catalogue as a back-end two-year-old, a winner and twice-placed in nine races up to 6f, and was sold to trainer Norah Wilmot for 500gns. Once more he lived up to his name, for after this public appearance at Park Paddocks in Newmarket, he was never seen on a racecourse again. Appropriately, perhaps, given that Tattersalls never sold another yearling at Doncaster.

Published on 9 September 2017inFeatures

Last updated 12:21, 10 September 2017

- Government says it is working 'at pace' to have white paper measures in force by the summer

- 'The only thing you can do is lie fallow and regroup' - Meades to return with scaled-back operation following blank period

- The Gambling Commission has launched its new corporate strategy - but what are the key points?

- 'It was tragic it happened to Paddy but it was a good thing for the jockeys who followed - good came out of bad'

- Acquisitions, exits and retail resilience - what we learned from Flutter and 888's results

- Government says it is working 'at pace' to have white paper measures in force by the summer

- 'The only thing you can do is lie fallow and regroup' - Meades to return with scaled-back operation following blank period

- The Gambling Commission has launched its new corporate strategy - but what are the key points?

- 'It was tragic it happened to Paddy but it was a good thing for the jockeys who followed - good came out of bad'

- Acquisitions, exits and retail resilience - what we learned from Flutter and 888's results