Don't keep problems locked inside says family of former weighing room stalwart

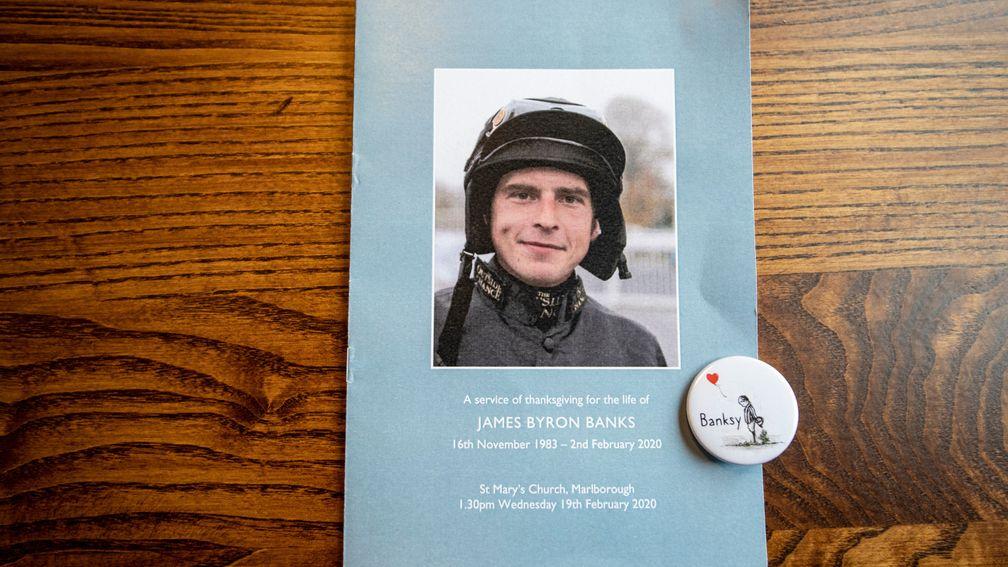

On a market day in Marlborough three months ago, a church was filled to capacity for the funeral of James Banks. So many of the mourners had memories of the former jockey as a bubbly, funny, gregarious character. A small percentage had known the other James. It was for that reason his mother had long since seen the day coming.

Beverley Reid chose not to attend the inquest, at which the subject of her son's personal finances was raised. They were not in a marvellous state but Beverley wants to stress there were many factors that contributed to James taking his own life, all of them wrapped inside his long-term mental illness. She also wants to speak about that illness to potentially help others during this year's Mental Health Awareness Week.

"I wake up every day thinking it’s only just happened," says Beverley. "I keep expecting him to walk through my door, give me a big hug and raid my fridge. I want people to know about James because they could be suffering from the same things he did."

Beverley, who works as a nurse, had watched with pride as Banks went through a riding career that yielded 85 victories. The career ended on February 2, 2018, almost exactly two years before the life was brought to an end.

"I knew one day something like this would happen," says Beverley, who had first become seriously alarmed when Banks, then aged 17 or 18, suffered a "a significant psychotic episode" while staying with his father, Martin, in Newmarket. Although he recovered, going on to establish himself as a popular and respected member of the jumps weighing room, the point at which he left that room for good was always going to be fraught.

"I knew he would find life after riding difficult because it had been his life for so long," says Beverley.

"Things definitely became worse after he retired. I don't think deep down he wanted to finish but he had a bad fall at Chepstow a few months before he stopped and it knocked him unconscious. He said he felt he had gone through a near-death experience. It frightened him and it took some time for him to get over it. I don't know, though, how long he spent thinking about retirement because one of the things about James was he didn't say a lot about how he felt."

Even without expressing his feelings, Banks began to make it obvious all was not well. Not long after he retired there was another psychotic episode.

"He was aggressive and he was drinking – it was like talking to an empty body," remembers Beverley, who provided constant support, more of which came from Professional Jockeys Association chief executive Paul Struthers and Injured Jockeys Fund almoner Clare Hill. At one point Banks contemplated a return to riding in France and therefore stopped taking helpful medication because, for jockeys, it was a banned substance. Problems mounted and his anxiety levels rose. So, too, did the fears of his mother.

"James went down to Gloucester last August to see his auntie," she says. "One day I was upstairs looking for something in the room James had been sleeping in and I found a letter. At the top of it were the words: 'Dear Mum'. I didn’t read any more because I knew what it was going to say.

"I phoned James and told him I had found the letter. He told me I hadn’t been meant to see it and assured me he was okay.

"He came back home and I didn’t tackle him about it again, but for a long time I didn't go to bed without having a horrible feeling in my head. When I had the phone call to tell me what had happened, the first words I said were: 'It’s James, isn’t it?'"

In the second half of last year Banks took a job at the Naunton stables of friend Emma-Jane Bishop. His mother visited him in November and felt he looked like "a shell". Her concern increased.

"I knew then he was getting bad," she says. "Three weeks before he died I became really worried he was going to do something. I could tell he wasn’t right. I spoke to him on FaceTime the Saturday before he died and then the following day he saw his dad in Gloucester. We both knew how depressed James had become. His dad said to him: 'You're not going to do anything stupid, are you?' He said he wasn’t - but then that night he did what he did."

Beverley adds: "He started the suicide letter in October. He wrote it as if that was going to be his last day but then he carried on and wrote another letter, again as if that was going to be his last day.

"He wrote about how he had struggled, how he felt a failure and how he thought he had let his family down. It was so detailed. He couldn’t live with himself and he couldn’t live with his mind because of all the nasty thoughts that came into it. He said he didn’t want to go back to drinking and taking drugs but he couldn’t live sober with ‘this stuff’ in his head. I think he did it out of sheer desperation."

The illness that claimed Banks has ensured a sense of despair remains, this time in the hearts and minds of those he left behind.

"I think people are sometimes sadly too proud to seek help," says Beverley.

"Nobody should be ashamed of mental illness. It is so common now but people often hide it very cleverly. That’s what James did. He always seemed to be a very outgoing person but he only told people what he wanted them to know. He was the life and soul of a party but that just covered up his issues. He put on a happy face."

At his funeral there were tears aplenty but also happy memories of a man whose brother, Ryan, described as his idol and prompted plenty of laughs when telling the congregation: "James's life had so many ups and downs, whether it was over a fence or under a sheet."

Now, three months on, Ryan Banks has a message.

"There are always highs and lows," he says. "James achieved many great things in his life but there were also choices he made about which he wasn’t proud – none so bad he couldn’t have come back from them, but in his head he had fallen too far.

"We would encourage anyone who is struggling in any way to speak to someone. Be honest about how you are feeling and seek the mental health support you deserve."

Confidential support and counselling helplines are available 24 hours a day via the Professional Jockeys Association (07780 008877) and Racing Welfare (0800 6300 443)

The Banks family has launched a fundraising page on the Memory Space website of mental health charity Mind

Published on 22 May 2020inFeatures

Last updated 16:40, 18 June 2020

- Government says it is working 'at pace' to have white paper measures in force by the summer

- 'The only thing you can do is lie fallow and regroup' - Meades to return with scaled-back operation following blank period

- The Gambling Commission has launched its new corporate strategy - but what are the key points?

- 'It was tragic it happened to Paddy but it was a good thing for the jockeys who followed - good came out of bad'

- Acquisitions, exits and retail resilience - what we learned from Flutter and 888's results

- Government says it is working 'at pace' to have white paper measures in force by the summer

- 'The only thing you can do is lie fallow and regroup' - Meades to return with scaled-back operation following blank period

- The Gambling Commission has launched its new corporate strategy - but what are the key points?

- 'It was tragic it happened to Paddy but it was a good thing for the jockeys who followed - good came out of bad'

- Acquisitions, exits and retail resilience - what we learned from Flutter and 888's results