Brawls, bribery and bedlam at the Palio, the world's most chaotic race

Tom Kerr soaked up the madness and mayhem of the Palio di Siena, a tradition stretching back to medieval times, during a tour of Italy's greatest racing landmarks. The Palio formed the centre piece of a three-part series available to Ultimate members. First published Monday, July 10, 2018.

Horseracing is not without its oddities – think the Velka Pardubicka with its ploughed field, the Anjou-Loire Challenge in which horses hurtle down a near vertical cliff, or any cross-country race at Cheltenham – but the modern sport cannot come close to matching one medieval race in Tuscany for sheer unadulterated lawless chaos.

The Palio di Siena, which takes place twice each summer, has been going on since 1633, although its antecedents stretch back centuries before that. It features ten horses, each representing neighbourhoods of the pretty walled city, thundering thrice round the central square on a track of packed sand, jockeys thwacking each other with their whips – which are made from stretched ox penises, by the by – as they go.

The term lawless is not used lightly. The Palio has no rules of consequence. Riders are free to barge, to whip, to interfere as they please. What's more, the race is determined more by corruption than by skill. This is not, though, some plague of dishonesty to be stamped out by whatever the Sienese version of the BHA is. Much of the bribery takes place in the open, before the race, as jockeys offer their rivals payoffs to assist them in the race. Bribery is not just tolerated at the Palio, it is celebrated.

As one former rider put it, the Palio is not a race but a game, and it is a game which means everything to the people of Siena. The 17 neighbourhoods, or contrade, which comprise the city trace their lineage to the Middle Ages, when Siena was a republic fighting to avoid being annexed by its pushy neighbour to the north, Florence. That fight was lost, but the contrade live on – traditional, independent and fiercely proud.

Each contrada has a name – mostly animals, like Giraffe, Goose, and She-Wolf – a flag, constitution, elected officials and they engage principally in enthusiastic corruption. In this they are roughly analogous to local government the world over. These contrade all have allies and adversaries among the other neighbourhoods; some rivalries are so strong it is considered good sport to lose a Palio if in doing so a reviled neighbour's chances are sabotaged.

Planning for the Palio goes on throughout the year, with each contrada's elected captain and his lieutenants merrily fundraising and bribing through the winter and spring, but excitement and activity reach a pinnacle in the days leading up to the race, when the track is laid in the Piazza del Campo, the central square.

The Campo track could charitably be described as a death trap. Run around the outer edge of the square, it is 339 metres in circumference and navigated three times by the ten runners (ten is the safety limit – to allow all 17 to race would be dangerous). The shape is roughly semicircular, with the most notorious feature being the curve of San Martino, a terrifying downhill 95-degree turn at the track's north-east corner where runners and riders are frequently slammed into a padded wall on exit.

After navigating this hair-raising corner, the next challenge for riders is to avoid the Cappella di Piazza, an imposing marble chapel that projects far out into the track mere metres after San Martino. The chapel was built in 1348 by the grateful survivors of the Black Death and it is a profound irony it now seeks to cripple and maim Palio riders.

One other intriguing aspect of the Palio is that it is the horse who wins, not the jockey. As such, riders do not need to actually be on board for a horse to triumph – indeed, riderless horses have won many races, most recently Giraffe in 2004.

This might be said to indicate the low regard in which the Sienese hold their jockeys. Since the riders are contracted to the contrade and are in fact the only paid representatives in the entire affair they are popularly held to be soldiers of fortune, mercenaries, lauded if they win but scorned as liars, cheats and dogs if they lose (it is the same the world over, sure). Naturally, no crime is considered more heinous, more indicative of underhandedness and low character, than finishing second.

Still, the riders hold the destiny of their contrada in their hands and their role should not be underestimated. They must have skill – yes. Courage – plenty of it, for serious injury is common. But perhaps the most important characteristic is guile, for it is the rider who carries out the most important slice of bribery of all.

This takes place immediately before the start of the Palio. Given that the track makes Chester look sweeping and fair, the draw, announced only once the riders are at the start, is vitally important. Nine of the ten runners are called into the starting area, where they line up without stalls beyond a thick rope and proceed to jostle, punch and whip each other with abandon. The final representative is the run-in rider, whose entrance to the starting area launches the madcap race.

As the runners are inevitably asked to leave the starting area – nominally because the jostling gets out of hand, but I suspect in reality to facilitate what follows – the riders gather around the run-in fellow and openly attempt to bribe him in front of thousands of spectators. Such is the fashion in these parts.

The most celebrated – or reviled – current jockey is Luigi Bruschelli, known as Trecciolino, winner of 13 Palios (including one where he fell off) and widely considered a master of the Palio, in that such is his skill at the dark arts he could well have secured a prosperous living as an Italian captain of industry or government minister.

As I arrive in Siena the day before the race, I'm delighted to learn the wily Trecciolino has signed up to ride for my adopted contrada, Nicchio, a district in the far eastern corner of Siena where I am staying.

Nicchio has endured a sad time of it in the Palio of late. It last won in 1998 and in 2015, when it was well fancied to win, was caught up in controversy after the rider of its fierce rival, Valdimontone (Ram), leaned over and yanked its jockey off his mount mid-race. This led to outrage in Siena, although not at the act (rightly considered cowardly, although what can you expect from the dastardly Valdimontone?) but at the unsporting decision of magistrates to prosecute the rider for assault – he was later sentenced to community service.

The night before the Palio the contradaioli – that is, the people of the contrade – descend on the Campo for the prova generale, the Palio dress rehearsal, before returning to their contrada for vast open-air feasts in the street, with speeches, songs, flags and toasts upon toasts. Afterwards, the captains and lieutenants drift off into the gloom to meet with rivals and allies for one last hurrah of corruption. Since Nicchio has not won in so many years it should have built up a vast bribery fund and as I drift off to sleep I think happily of the mass corruption being enacted on our behalf.

Palio morning dawns bright and early. The race does not begin until 7.45pm but it is preceded by an array of historic and symbolic events, of which the most curious is the blessing of each horse by a priest in its respective contrada, after which the horse and its attendants proceed in high state towards the Campo.

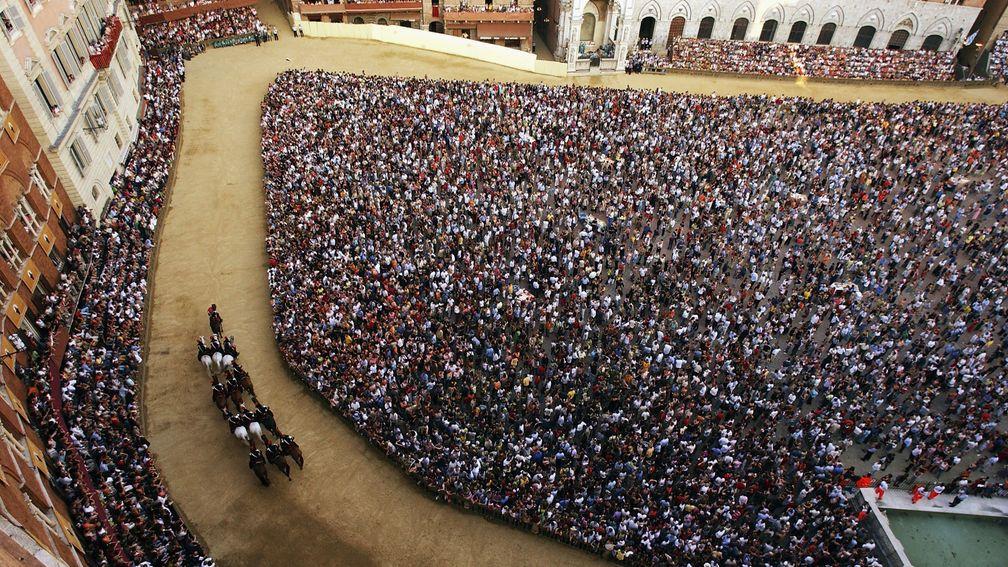

Ah, the Campo. It is possible to purchase seats on rickety looking bleachers surrounding the square or, if money is no object, in apartments overlooking the square (these trade hands for thousands of euros), but the true experience is to watch from the centre, where entry is free. I arrive to secure my pitch at 4pm, at which time the temperature in the sun is 38C. A wait of over four hours in the broiling heat and severe sunstroke beckons.

At length, the festivities begin: a parade and charge of carabinieri in full dress uniform, swords drawn; then a grand and solemn procession, the Corteo Storico, of contrade flags, with bearers dressed in medieval regalia and accompanied by drummers and men in plate armour.

The noise is tremendous. At any given point at least half a dozen different contrade drummers are playing in competition around the square, while a band in period regalia on one of the bleachers blares out the Palio anthem every few minutes.

In the north-west corner of the square, a huge mortar periodically utters an earth-shattering explosion, although I never do divine the significance or timing or it. Perhaps there is none, but it petrifies the American kids at every eruption, so I grow fond of it.

As the hour of the race approaches, the Palio itself enters. This is nothing more than a painted banner, created anew each year by a local artist, and is 'all' that the winning contrada receives for victory – such a relatively humble prize tells its own story about their motivations.

Nonetheless, it is piped into the square with great fanfare, pulled by a team of oxen on a cart of ancient design and accompanied by trumpeters, before being hoisted on to the judges' balcony, from which officials, local dignitaries and the contrade captains watch the race.

It is beneath this balcony the ten runners and riders gather for the race mere minutes later. Then follows the tensest moment of all, for which the entire square falls deathly silent: the draw for all-important starting positions. Oca, or Goose, one of the favourites, secures the coveted first position, while Nicchio is assigned fourth spot.

What follows is the most shambolic starting procedure of any race I have ever witnessed. Naturally there is the requisite jostling, taunting, ox penis tomfoolery and so forth, followed by a goodly period of honest bribery, but false start follows false start and the minutes slip by – 15, 30, a full hour. One older gentleman becomes so irate he scales the judges' balcony to politely upbraid the starter of his incompetence.

Just as it seems as if the race might even be delayed due to low light – such a thing can happen – the run-in rider suddenly accelerates into the starting area and the Palio is, at last, under way. Drago, handed the widest draw of all, gets by far the best start and launches into an unlikely lead (such a start must have cost many thousands of euros) as the field thunders towards the curve of San Martino for the first time.

Then, disaster strikes. Trecciolino, having got away in mid-division for Nicchio, takes San Martino wide and is rammed – rammed, I say – into the padding by the representative of those infamous villains, Valdimontone. Trecciolini tumbles agonisingly to the ground along with two other riders. The dream is over.

Drago, having secured a tremendous start, is never caught. Oca closes into second but cannot catch the leader, who hurtles round the three laps in just 90 seconds and waves his ox penis in triumph as he flies by the winning post, delirious Drago contradaioli spilling on to the track in utter jubilation. The mortar fires repeatedly, all is bedlam.

Then, on the other side of the Campo to me, a mass brawl breaks out between rival contrade – it is, of course, the Nicchio faithful turning their just ire on those knaves from Valdimontone.

Fists fly as dozens of contradaioli pile in on each other. After several minutes of this entertaining brawl, the carabinieri stroll leisurely towards the disturbance to observe at closer quarters. Truly, this is community policing at its finest: let the lads tire themselves out then round up a few stragglers.

Meanwhile, the jubilant contradaioli of Drago are singing and celebrating in unbounded joy, the winning jockey, known as Brio, hoisted on to shoulders and feted as a hero. Their celebration will go on long into the night – in fact, it will go on for an entire year. That is what a Palio victory means to the people of Siena: it is bragging rights, it is ancient rivalry, it is history in the making.

A visitor to the Palio can never truly understand the significance of the race, but just 48 hours in Siena – enough time to witness the passion, the pageantry and the madness – gives one an inkling of what it all means. Ultimately, it is about identity – identity fiercely guarded, loved and nurtured.

Siena was an independent republic in the Middle Ages. It had a government of her own, armies under her banner and great wealth. Ravaged by the Black Death, it was at last eclipsed by Florence and its independence snuffed out nigh on 500 years ago. This might have been a death knell as deadly as any plague for the Sienese; the moment they were relegated from proud independent people to a sleepy Tuscan backwater, just another footnote to history.

Instead, Siena's identity has prospered, grown profound and meaningful as the centuries have passed and greater cities have lost what it meant to be a community. Today, it can be fairly said that Siena has held on to its identity, customs and history more firmly and more fervently than almost any other city on Earth. And it has to thank for that, of all the great and good things in this strange world of ours, a horse race. What a wondrous thought, what a marvellous place.

This article is available free as a sample. Members can read exclusive interviews, news analysis and comment available from 6pm daily on racingpost.com

You can read Tom Kerr in the Racing Post every Friday or online from 8pm on Thursday

Denman reminded all us devotees it is the legends who sell racing best

Minimum margin proposal would be bad for punters – and bad for racing

O'Brien will be back better after bruising experience at chaotic Kentucky Derby

Published on 17 July 2018inFeatures

Last updated 13:18, 17 July 2018

- The Gambling Commission has launched its new corporate strategy - but what are the key points?

- 'It was tragic it happened to Paddy but it was a good thing for the jockeys who followed - good came out of bad'

- Acquisitions, exits and retail resilience - what we learned from Flutter and 888's results

- The classic star named after Steve Harley: how Cockney Rebel proved to be a life-changer

- 100 years of the Gold Cup: John Randall ranks the greatest winners - and the worst

- The Gambling Commission has launched its new corporate strategy - but what are the key points?

- 'It was tragic it happened to Paddy but it was a good thing for the jockeys who followed - good came out of bad'

- Acquisitions, exits and retail resilience - what we learned from Flutter and 888's results

- The classic star named after Steve Harley: how Cockney Rebel proved to be a life-changer

- 100 years of the Gold Cup: John Randall ranks the greatest winners - and the worst