The occasional places where man and horse take on mountain, sea, sand and city

Peter Thomas on the so-called racecourses that exist for only a few days a year

Laytown

The best-known bout of racing barminess in the British Isles. One minute it's a racecourse in County Meath, Ireland – the last remaining site for beach racing in the country – the next it's a wholly submerged segment of the Irish Sea, unsuitable for a sizeable crowd with a sense of self-preservation.

Racing on the strand at this coastal amphitheatre, to the north of Dublin and just to the south of Drogheda, was first recorded in 1868, when the meeting was run in tandem with the Boyne Regatta – the rowers presumably putting on their show at high tide and the horses at low tide, although the other way around might have made for good viewing.

While the Bishop of Meath apparently disapproved, members of the local clergy took over the running of the races at the turn of the 20th century and they thrived, as at many other similar venues around Ireland, with the sands being regarded – in the 1950s and 60s, before the advent of all-weather surfaces – as ideal preparation for the Galway festival.

Races, once run over a substantial trip with a U-turn in the middle, are now contested over a straight six and seven furlongs and – since a catastrophic incident involving a bolting horse in 1994 – with the crowd behind barriers and under the auspices of health and safety.

The next meeting will take place on Wednesday, September 11 with an approximate start time of 4pm. Please consult local tide tables.

Birdsville

About as far from Laytown as a racegoer can get, in every sense. Birdsville is a remote town in Queensland, Australia, which enjoys a hot desert climate, with temperatures rising to a little shy of 50C. In September, however, the region slips to a cool 40C and welcomes around 6,000 people to join the 100 or so residents for a two-day race meeting that has been held since 1882.

Some come by dusty road, many others by air, for a carnival that raises funds for the Flying Doctor service, provides a welcome economic boost for the owner of the local caravan park, and prompts a street party on the main drag of the nearby town of Quilpie, designed to entertain visitors from the east coast who have endured a ten-hour journey to get there.

Despite Birdsville routinely having just 22 days of rain a year, the 2010 running was abandoned due to flooding of the makeshift dirt track, while 2007 was called off due to equine flu, but otherwise travellers are treated to what the Queensland tourist people describe as 'Two days of quality outback racing and entertainment – the second race meet in the Simpson Desert Racing Carnival' (in conjunction with Bedourie and Betoota).

The next meeting will take place on September 6 and 7.

Litang

If remote and exotic is what you’re looking for, then the Tibetan Horse Racing Festival is your destination, where modern-day nomadic herdsmen or khampas dress up like their ancestors for a gathering of the clans at two dramatic venues, with plenty of horse trading, traditional food, drink, singing, dancing and red-blooded equestrian action.

The meeting held in the monastery town of Litang, in the uplands of eastern Sichuan Province in the first week in August, is reckoned to be the real deal, relatively untouched by the clammy hand of tourism. Held on grassland ideally suited to long-distance racing and pitching tents, it bears little resemblance to Royal Ascot and the racing, untroubled by BHA regulations, is not for the faint of heart.

The conveyances are small and speedy Tibetan ponies and victory is a matter of no little honour among the tribes of the Tibetan plateau, who will no doubt puff a little less than the tourists at an elevation of some 4,000 metres.

Sanlucar de Barrameda

If Ireland should ever run away with the notion that it was the first nation to race horses on a beach, the Spanish might have something to say about it. In the town of Sanlucar de Barrameda, deep in the Cadiz region of the south-west of the country, near the wild Atlantic coast, they've been doing very much the same thing since 1845, maintaining the age-old tradition of the fish merchants of years gone by, who used to ride with their daily catch to the market.

Before the formation of the Sociedad de Carreras de Caballos de Sanlucar de Barrameda, it was a battle of pure economics – based on who would be the first to begin selling their wares – now it's a popular tourist attraction consisting of two events, each lasting for three days, at low tide in the afternoon. Unsurprisingly, the races form part of a festival of song, dance and cultural exuberance in honour of the patron saint, combined with the exhibition of a carpet of flowers in the city streets.

This year's meetings will take place on August 9-11 and 25-27.

Piazza del Campo

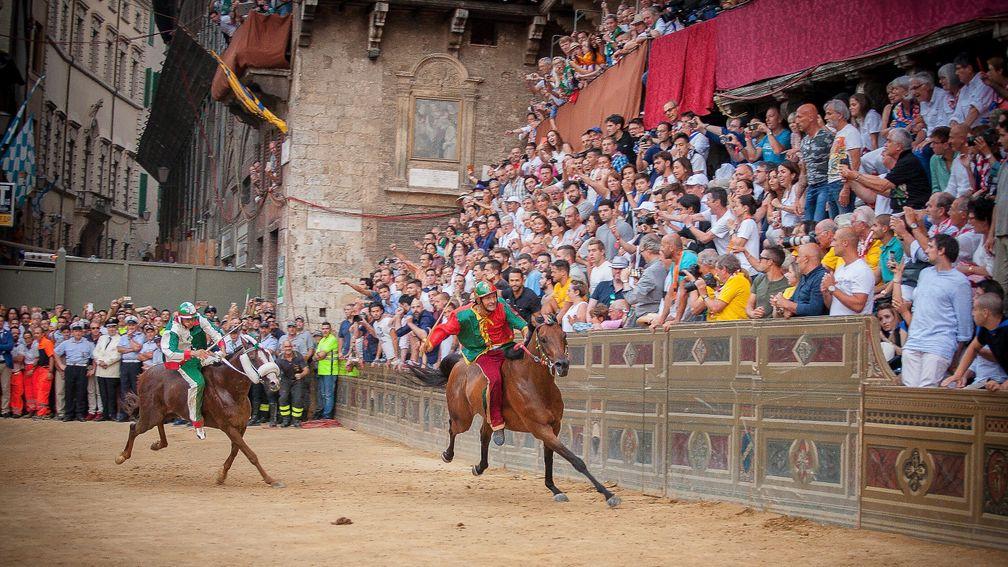

Racing horses against a backdrop of the incoming tide may be slightly off the wall, but for sheer equestrian insanity look no further than the Italian region of Tuscany, where the ferocious Palio di Siena is staged twice a year round the city's central Piazza del Campo.

Similar events across the city were run in the 14th century, with the banning of bullfighting in 1590 proving the catalyst for the modern Palio, which still involves fierce competition between the local 'contrade' or city wards, although the intensity of the feuds has been toned down by the restriction, in 1729, of the number of runners to just ten, owing to the number of casualties.

These days, the piazza is rendered almost safe by the laying of a thick layer of dirt and the planting of padded crash barriers; conversely, the bareback riders are still allowed to use their whips on the mounts of other riders and a horse can still be declared the winner even if its rider has been decanted during the three laps, roughly 75 seconds, of the race.

With mounts chosen by lottery and rivalries fierce, competition is white hot and corruption widespread, despite the fact both races each year are run in honour of the Virgin Mary in front of 60,000 people.

The first Palio of the year is held on July 2, the second on August 16.

Royal Park, Stockholm

While racing in the city hasn't yet taken off in London, in the Swedish capital a once-a-year meeting has established itself as a firm favourite on National Day, in June, over the past six years.

Think Hyde Park but in the middle of Stockholm, with free entry, a festival atmosphere, live acts, prizes for the best hat, but with racing at the heart of it all and crowds of up to 60,000. Last year there were four thoroughbred races, two Arab races and two pony races, with plenty of prize-money and four wins for female riders, all broadcast on national TV.

Perhaps racing past Buckingham Palace isn't such a daft idea after all.

Lake St Moritz

If the heaving masses of Siena are too much for you, then why not repair to the most famous seasonal racecourse of them all, the White Turf of St Moritz, which as you may have guessed, although it is white, has very little in common with turf.

Racing at this swankiest of Swiss ski resorts, at an altitude of 1,768 metres, takes place on three Sundays in February on a lake that, thankfully, remains frozen for the duration (normally) and covered in snow. The seven-race cards are divided between Flat racing, trotting and skikjoring, in which the 'jockeys' are pulled along behind their horses while wearing skis.

Staged since 1907, this playground for the rich, famous and beautiful – and others – remains a prestige event in the racing calendar and regularly attracts crowds of 10,000 and plenty of runners from Britain, although there is no truth to the suggestions that trainers enter their horses simply for a subsidised, champagne-fuelled skiing weekend with their other halves.

When there is no racing scheduled, Lake St Moritz is used for polo (played, of course, with a red ball) and occasionally cricket (likewise). Visitors used to be allowed to park on the lake but . . . well, what could possibly go wrong?

More seaside fun

St Moritz too chilly? Let's go back to the beach and explore the multitude of options across Europe. We've done eastern Ireland and southern Spain, but there are less celebrated events held at La Laredo (May) and Loredo (July), both in Cantabria, northern Spain; at Cuxhaven, on the mudflats of the Elbe estuary in north Germany (July); and at Plestin-les-Greves (July) and Plouescat (August) on the Brittany coast in France.

With these natural sand tracks now covered by the umbrella (or parasol) of the European Beach Racing Association, racing-mad travellers can easily plan a summer gambling extravaganza in the guise of a family touring holiday.

The course at Duhnen beach near Cuxhaven has staged racing since 1902 and attracts 30,000 racegoers a year. The track at Kernic Bay, on the Cote des Sables in Brittany, is celebrated in song by fellow Celts Gaelic Storm, who recorded The Plouescat Races for their 2001 album Tree.

Mongolian Steppe

Sheikh Mohammed is well known for his love of endurance racing amid the sand dunes of the Middle East, but even he would marvel at the Mongol Derby, a 1,000km jaunt across unforgiving terrain, which since 2009 has brought a little touch of Ghengis Khan back to the Mongolian Steppe.

The course is a closely guarded secret until just before the race, which can't help spectator numbers, but it will always involve mountains, valleys, rivers, dunes hills and broad expanses of steppe. Luckily riders can call upon a host of horses and a support team, with vets posted along the trail for welfare purposes.

Competitors may spend 14 hours a day in the saddle for ten days on part-wild horses who have scant regard for regulations and etiquette, which explains why only half of the 40-odd riders from a dozen or so countries are expected to finish the race.

It's definitely not a racecourse but it's a hell of a race.

Get exclusive insight from the track and live tipping with Raceday Live - our up-to-the-minute service on racingpost.com and the Racing Post mobile app

Published on 21 March 2019inSeries

Last updated 13:37, 21 March 2019

- We believed Dancing Brave could fly - and then he took off to prove it

- 'Don't wind up bookmakers - you might feel clever but your accounts won't last'

- 'There wouldn't be a day I don't think about those boys and their families'

- 'You want a bit of noise, a bit of life - and you have to be fair to punters'

- 'I take flak and it frustrates me - but I'm not going to wreck another horse'

- We believed Dancing Brave could fly - and then he took off to prove it

- 'Don't wind up bookmakers - you might feel clever but your accounts won't last'

- 'There wouldn't be a day I don't think about those boys and their families'

- 'You want a bit of noise, a bit of life - and you have to be fair to punters'

- 'I take flak and it frustrates me - but I'm not going to wreck another horse'